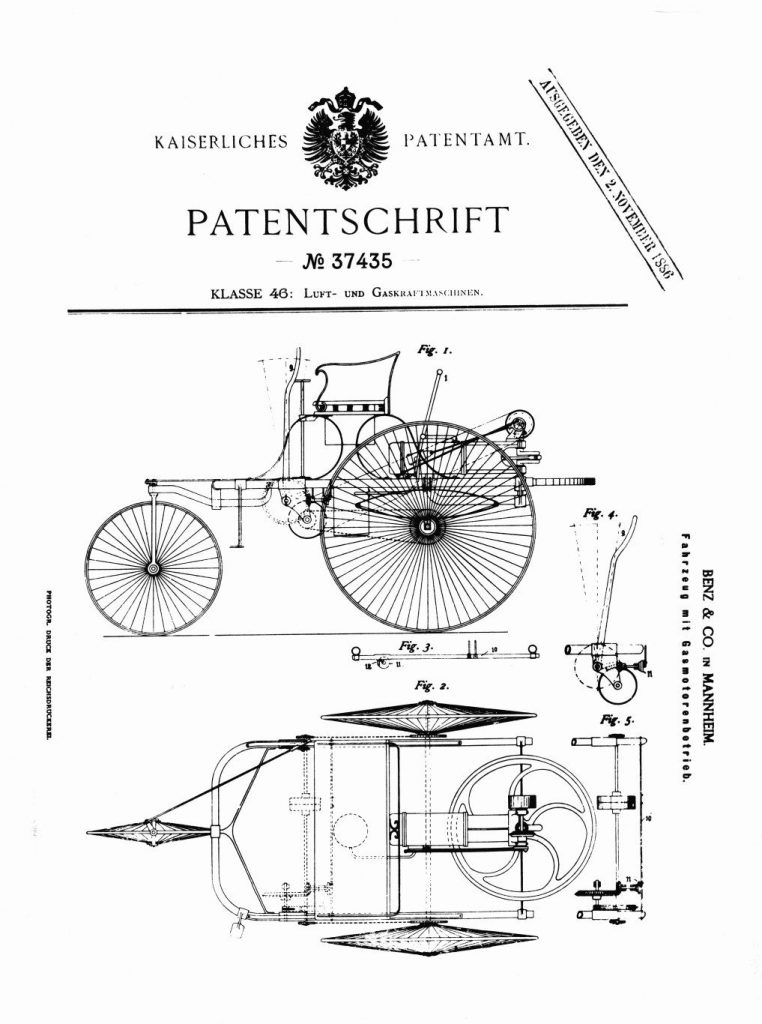

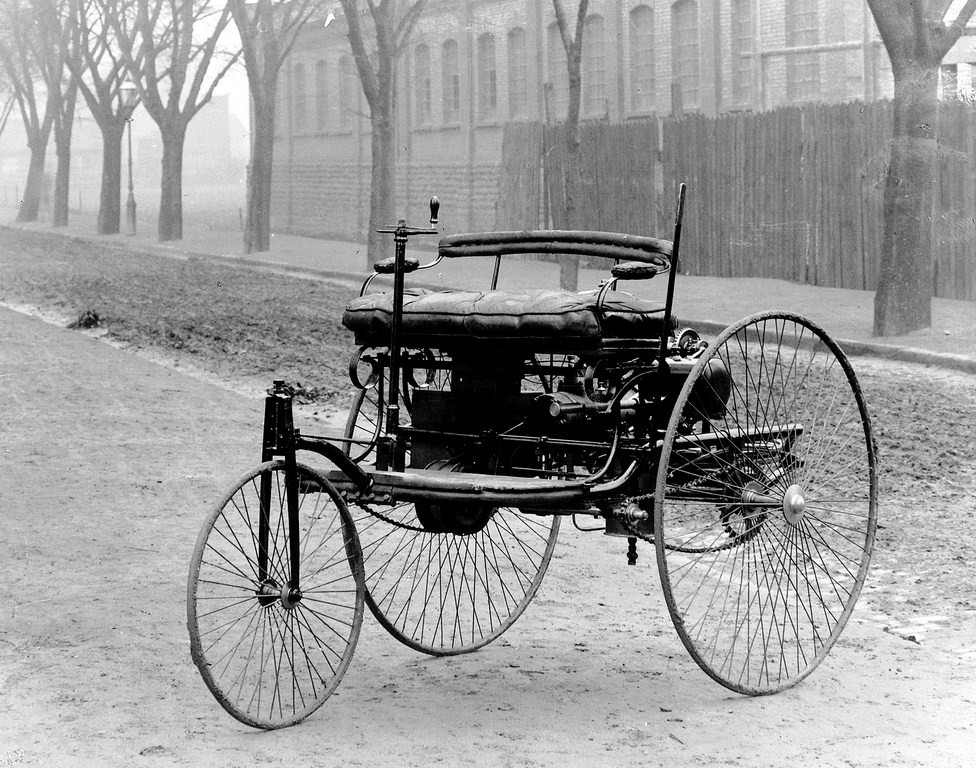

In the early morning hours of August 5, 1888, Bertha Benz and her two teenage sons, Richard and Eugen, rolled the first patented horseless carriage, or Fahrzeug mit Gasmotorenbetrieb, onto the drive ringing their home in Mannheim, Germany. Unbeknownst to her husband, Karl, Bertha was taking his three-wheeled contraption on a trip to her mother’s home in Pforzheim — a 60-mile journey that would later become known as the automobile’s very first road trip.

Karl had debuted the “self mover” on the short road in front of his workshop a few weeks earlier, piquing the curiosity of locals, but not attracting any buyers. The noisy machine was viewed as a mere novelty, certainly not as a new mode of transportation. Why, people wondered, would they trade in their trusty steed for a sluggish beast that guzzled foul-smelling fuel? Horses were plentiful, hay was abundant and cheap, and there were no paved road networks to speak of. The world just wasn’t ready for Karl’s motor coach.

Karl may have been a gifted engineer, but he was at a loss when it came to convincing a skeptical public that a motorcar was a useful invention. Some say he lacked a complete vision for his vehicle, but Bertha had ideas of her own.

Having financed her husband’s car operation with her dowry, Bertha was determined to ensure his enterprise would succeed. To capture the public’s attention, Bertha knew she had to take the driver’s seat, literally. A few weeks after the horseless carriage debuted to those lackluster reviews, Bertha left a note for her sleeping husband and set out to prove the vehicle’s viability for long-distance travel.

The trip wasn’t easy. It took Bertha and her sons through steep and rugged terrain. They had to push the “smoking monster” up the muddy hills

a 60-mile journey that would later become known as the automobile’s very first road trip

through Heidelberg to Wieslock and repeatedly fill the engine with solvent purchased at local pharmacies. When the motor clogged and overheated, Bertha proved herself a clever mechanic. She cleaned the carburetor with a sharp hat pin, insulated a hot wire with her garter, and hired a local cobbler to nail leather liners on the brake blocks. She then motored on.

Dirty and exhausted, Bertha and her boys arrived at her mother’s home that evening and telegraphed Karl to announce their success. Their motorcar had finally caught the eye of onlookers and the press. Bertha’s road trip made headlines around the world, setting the stage for a new era of motorized transportation and the future success of the Mercedes Benz motor company.

It’s no surprise that Karl’s test drive failed to capture the world’s attention as Bertha’s trip had.

trip had. At the time, the horse was a mainstay of modern life, and commerce and culture were deeply interconnected with literal horse power. Horses moved people, freight and machinery across Europe and the United States. And a wide range of people made their living from the equine population: Teamsters, streetcar operators, carriage manufacturers, saddlers, stable keepers, horseshoers, buggy whip makers, veterinarians, streetcleaners, and the farmers who grew hay.

Swelling urban populations drew horses and the industries that supported them to the cities. They were so prevalent in urban centers that in 1888, a Boston banker was likely to encounter more horses than a cowboy in Texas.[1] Between 1870 and 1890, the U.S. teamsters’ numbers more than tripled, rising from just over 120,000 to 368,000 – jumping 311 percent in New York, 350 percent in Philadelphia, and a remarkable 675 percent in Chicago.[2] These horse-related jobs were vital to the economy of the day, and many in the public were suspicious of an invention that threatened people’s livelihoods.

Karl Benz may have developed a great invention, but Bertha and her boys were critical to breathing life into it. As Mercedes Benz’s first marketing team, they won over the horse-loving public with a publicity stunt that proved motorized transportation was safe, more sanitary than a horse, and above all else, not constrained by schedules and routes. The car also beat a horse’s pace and stamina, which at the time only clocked a top speed of about two to three miles per hour.[3] A car required fuel and water to keep going, but it didn’t tire.

Bertha’s road trip teaches us an important lesson about successful innovation. While the world loves to celebrate singular visionaries, no one is truly “self-made” – each innovator’s success hinges on the investments and contributions of family, friends, colleagues, teachers, and mentors. It’s the teams of people that support and toil behind them that get big ideas off the ground.

Bertha’s road trip also shows us that creativity thrives when people build ideas together. The best breakthroughs sometimes come from iterative thinking and leaps across a logical divide, which requires a high level of trust and team chemistry. When it comes to innovation, two heads really are better than one.

But perhaps more than anything else, the car’s first road trip is a powerful reminder of the contributions made by women long before their role was widely recognized in society.

At a time when women were mostly sequestered to domestic duties, Bertha was a courageous pioneer. She embarked on her journey when paved roads, street signs and filling stations didn’t exist. And while the car had passed a short trial run, Bertha wasn’t entirely certain that the vehicle could make the trip to her mother’s home. Not only did she prove that the vehicle worked and had a future, but she showed the world that a woman was capable of driving it.

There’s a bit of irony in the fact that it took a woman to show the world what a car could do. It wasn’t until the late 1920’s that it was really acceptable for women to drive and it took almost a century later, in 2014, for the number of women with driver’s licenses in the United States to finally match (and then exceed) the number of men. In a year marked by the recent popular success of the movie Hidden Figures – the story that revealed the role women played in NASA’s success – it’s obvious that Bertha Benz was not alone in her contributions to innovation.

As we hit the highway on our own late summer road trips, it’s a good time to reflect on Bertha’s achievement. Her drive more than a century ago reminds us that innovation takes a village, or at least a family in Mercedes Benz’s case. And it shows us the opportunities for future innovation that come from bringing more diversity and an inclusive and creative workplace to the world of technology.

Not only did she prove that the vehicle worked and had a future, but she showed the world that a woman was capable of driving it.

Today in Technology is a series that highlights important technology developments from the past and discusses

the insights they offer for the tech trends and issues of our own day.

[1] Ann Norton Greene, Horses at Work: Harnessing Power in Industrial America (Harvard University Press, 2008)

[2] Clay McShane and Joel Tarr, The Horse in the City: Living Machines in the Nineteenth Century (John Hopkins University Press, 2007)

[3] Clay McShane, Journal of Transport History (Sage Publications Inc., 2003)