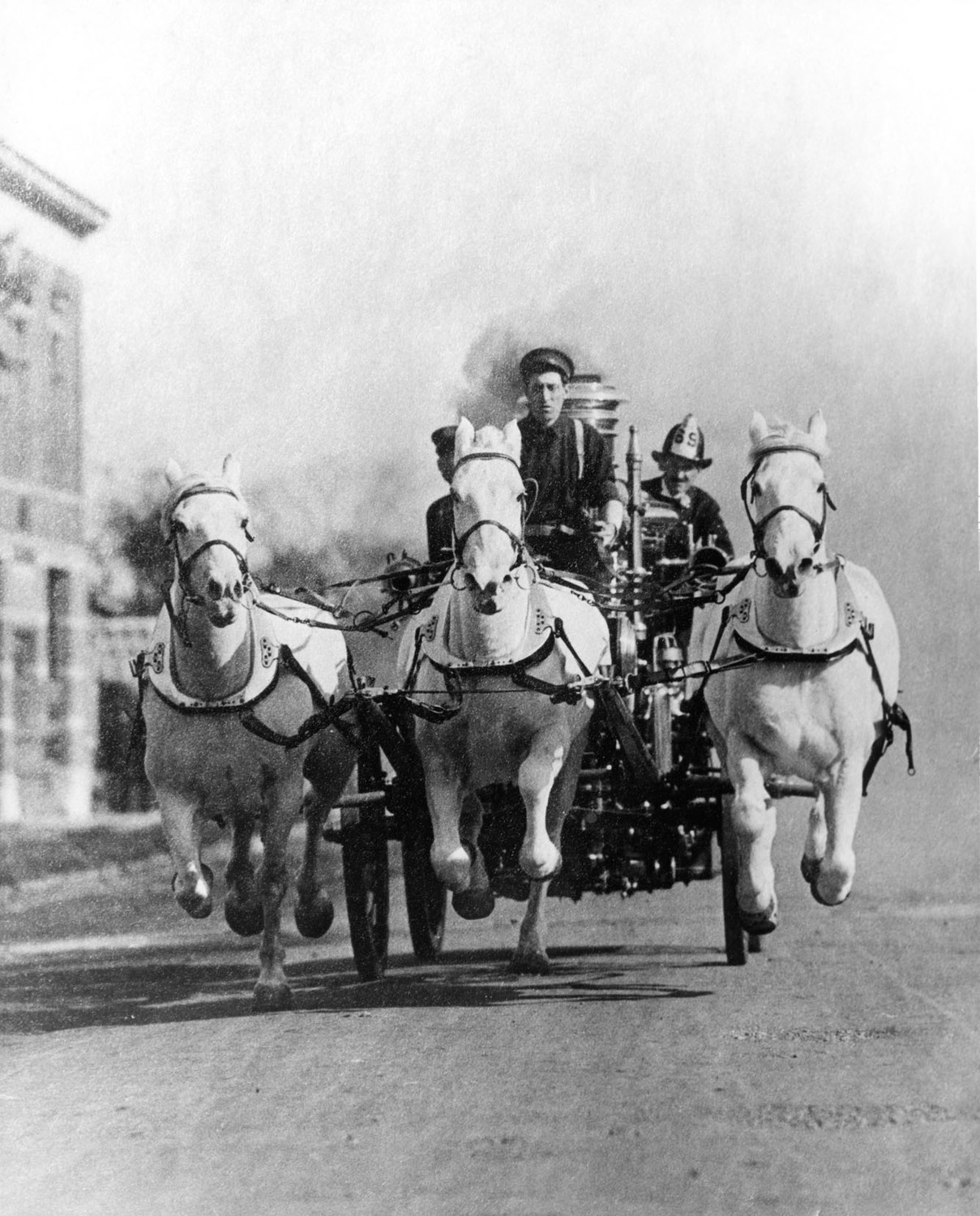

On December 20, 1922, the sound of restless neighs and the stamping of hooves echoed in the streets of Brooklyn Heights as Fire Engine 205’s finest strained against their hitches, eager to charge into the cold winter morning. Assistant Fire Chief Joseph “Smokey Joe” Martin rang the alarm bell at the station, signaling the company’s “first whip” John J. Foster to climb aboard the engine, pick up the reins and drive his eager team of horses out into the streets of New York City.

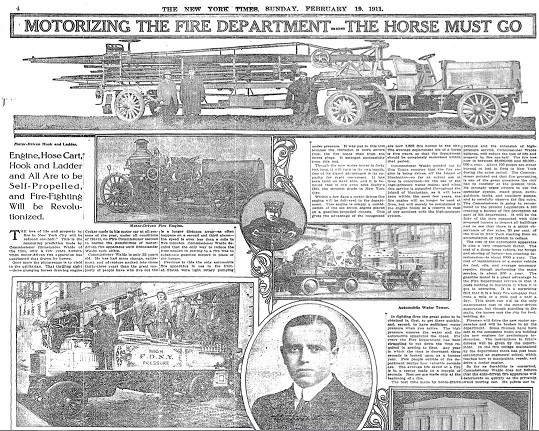

But there was no fire. The team was heading towards a ceremony at Brooklyn Borough Hall, where a sleek new motorized engine was waiting to formally replace the horse-drawn engine.

As the iron steam engine and hose wagon clamored through the city, New Yorkers lined the streets to cheer and chase after the horses as they charged down the roadway. The fire commissioner, Brooklyn Borough president, firefighters, city officials and Jiggs, the firehouse’s spotted Dalmatian, had turned out to pay tribute to Engine 205’s last “faithful and true” fire horses – Eamybeg, Buck, Penrod, Waterboy and Bellgriffin – for their years of service. [1]

It was an emotional moment for the station’s usually stoic crew. They were “a hard, two-fisted gang of firemen, afraid of nothing, as they have proven time and again, and they are not given to sentimentalities. But, under cover of banter and joking, their attachment for their equine co-laborers could easily be seen. The animals were polished until their sleek fur fairly shone.”[2]

As the drenched, heaving team pulled up to the hall, Jiggs anxiously circled the fire engine, prodding the men to hook the hose up to a hydrant.[3] Instead, firemen lovingly watered, groomed, and draped the five horses with wreaths of flowers. It would be the team’s final call – and the final run for all fire horses in New York City. After more than 50 years of service, the fire horse had lost its job.

While putting the fabled fire horse out to pasture was a practical matter, progress, as the Brooklyn Eagle wrote, had a profound impact on the city’s culture. “To the small boys of three generations the fire horse has been a delight as the fireman has been an inspiration. Today the fire horse vanishes in New York City, probably forever.”[4]

The introduction of horses in the firehouse was itself a controversial innovation that had been fought tooth-and-nail by traditionalists. Originally, fire engines had been pulled by volunteer teams of men and boys. But in 1832, when the Fire Department’s force was depleted by the city’s cholera epidemic, horsepower came to the rescue. “Not enough men, nor even supernumeraries, boys, and youths who loved to linger in the shadow of the engine house and be permitted to mingle with the hardy fire fighters, could be mustered to drag the engine to the scene of the conflagration.” Necessity, being the mother of invention, forced the FDNY to spend a hefty $864 on a fleet of horses to replace the sick and dying fire men.[5]

It wasn’t until the 1860s that manpower was officially swapped for horsepower in firehouses. But the transition wasn’t easy. One obstacle was the fire fighters’ pride in their work as haulers. Abraham B. Purdy, “one of the oldest living firemen” when interviewed in 1887, recalled, “The first company that ever had a horse to run was Hook and Ladder No. 1. The introduction of horse power was owing to a squabble in the company, which resulted in the resignation of so many members that not enough remained to draw the truck to a fire. No. 11 (Purdy’s company) was the means of killing that horse. There was a fire up in Broadway, and we and Hook and Ladder No. 1 ran side by side. Going up the hill at Canal Street was the proudest moment of my life. We beat the horse, and No. 1 did not get to the fire till sometime after us.”[6]

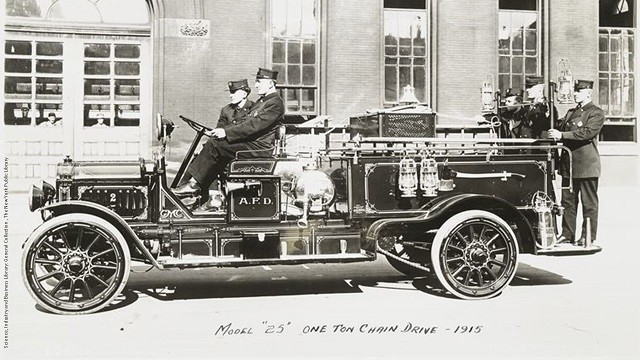

But advances in equipment and in the firehouse itself, including sliding poles, electric alarms and quick hitch horse collars, eventually allowed horses to relieve volunteers of their duties hauling hoses by hand. By 1869, well-trained horses and men could exit a firehouse in 30 seconds flat.

As the second Industrial Revolution churned to life in the latter 19th century, the new economy required the mass movement of people and goods. While inventors tinkered with engines of the future, the present relied on horses to do the heavy lifting of daily work, pulling trolleys, carriages, delivery carts, brewery wagons, city vehicles, and omnibuses.

The number of city horses swelled as did the peripheral industries that supported them: teamsters, streetcar operators, carriage manufacturers, groomers, coachmen, feed merchants, saddlers, stable keepers, wheelwrights, farriers, blacksmiths, buggy whip makers, veterinarians, horse breeders, street cleaners, and the farmers who grew grain and hay.

It’s difficult to overestimate the degree to which the American economy and broader society revolved around horses. As one historian has commented, “every family in the United States in 1870 was directly or indirectly dependent on the horse.”[7] In rural areas, farmers prospered in no small measure by growing hay to feed the nation’s 8.6 million horses, or one horse for every five people.[8] (And each horse ate a lot more than a person.[9])

In urban areas, the reliance was even more striking. This dependence hit home in the fall of 1872, when a serious strain of horse flu spread throughout the northeast U.S. and for some weeks horses could not be used. City life ground to a halt as streetcars stopped running, urban goods stopped moving, and construction sites stopped operating.[10] Consumers suddenly confronted shortages when buying groceries. Perhaps even more disturbing for some, saloons ran out of beer. There was nothing like the horses’ illness to demonstrate that such a large part of the American economy and its jobs revolved around horses.

The importance of the horse in fact continued to grow. Across the U.S., teamsters’ numbers rose from just over 120,000 in 1870 to 368,000 by 1890, more than tripling in just two decades. The number of street railway employees rose similarly over the same period — from around 5,100 to more than 37,000. Then, from 1890 to 1900, leading cities saw the numbers of teamsters skyrocket – jumping 311 percent in New York, 350 percent in Philadelphia, and a phenomenal 675 percent in Chicago.[11] In 1890, more than 90,000 people were employed by the wagon/carriage industry, producing more than 1 million vehicles, totaling USD $32 million, contributing greatly to the burgeoning economy.[12]

But beyond New York and the other big American cities, inventors were forging a new world, one which did not rely on horsepower. By 1908, entrepreneurs were producing cars in earnest and their work couldn’t have come at a more fortuitous time.

By the start of the 20th century, Americans had grown weary of the “disorder” of society and called for better sanitation, order, safety and, above all, efficiency. The hard-working horse seemed antiquated and a wasteful, dangerous means of urban transportation. In 1908, New York’s 120,000 horses produced a pungent 60,000 gallons of urine and 2.5 million pounds of manure every day on the city’s streets.[13]

Auto enthusiasts dreamed of a horseless city with “streets, clean, dustless and odorless, with light, rubber-tired vehicles moving swiftly and noiselessly over their smooth expanse, would eliminate a greater part of the nervousness, distraction, and strain of modern metropolitan life.”[14] It’s hard to believe that the utopia that 20th Century New Yorkers’ longed for is the gridlock and cacophony of horns that is modern day Gotham.

But beyond New York and the other big American cities, inventors were forging a new world, one which did not rely on horsepower. By 1908, entrepreneurs were producing cars in earnest and their work couldn’t have come at a more fortuitous time.

As Americans’ obsession with automobiles grew, their fondness for horses as a means for transportation declined. And the arrival of the car and electrified railways proved the horse’s death knell. People rapidly adopted mechanized transportation. In 1900, 6,000 horses hauled New York trolleys, more than all U.S. cities combined. But just 17 years later, the horse-pulled trolley took its last trip and the electric trams took over.[15] By 1902, 97 percent of America’s streetcar tracks were running on electricity. Motorized buses also stole routes from the horses, and in July 1907, the final horse-drawn coaches were replaced by the country’s first urban motor bus line. The five bright green automobile omnibuses that ran along Fifth Avenue may have cost 10 cents – double the cost of a horse-drawn fare – but were extremely popular.[16]

By the late 1910s, cities became inhospitable to the poor horse. Slippery asphalt was replacing dirt roads, neighborhoods began banning stables, and growers were opting for imported fertilizers instead of manure. As horses vanished, so did the numerous jobs that relied on the horse economy. In 1890 there were 13,800 companies in the United States in the business of building carriages pulled by horses. By 1920, only 90 such companies remained.

As the horse industry collapsed, another industry came to life. In 1903, the year Henry Ford founded Ford Motor Company, 11,235 automobiles were sold to Americans. Just a decade later, Ford flipped the switch on the first assembly line in 1913, cutting the time it took to build a car from 12 hours to 2 ½ hours. That year, the number of cars produced in the United States mushroomed to 3.6 million — a 300-fold increase since Ford founded his company. By 1923 the country was producing 20 million automobiles per year. And of course this fueled the growth for all the components and raw materials that went into the production and use of cars, from steel and rubber to glass, and oil.

By 1917, New York was the epicenter for the country’s automobile sales rather than urban horses. Shops that sold wagons, carriages, harnesses, and saddlery on Broadway were replaced by supply stores selling tires, ignitions, speedometers, batteries, and carburetors. Where the American Horse Exchange once stood, tall office towers owned by Benz, Ford, General Motors, and Oldsmobile sprung up. Repair shops, parking garages, gasoline filling stations and taxi companies were desperate for new, skilled talent to fill their ranks and support America’s growing obsession.

The U.S. auto industry created new companies and jobs – and a lot of them. According to the McKinsey Global Institute, between 1910 and 1950, the auto industry created 6.9 million net new jobs in the United States, equivalent to 11 percent of the country’s workforce in 1950. This includes 7.5 million jobs created and 623,000 jobs destroyed. These jobs represented new occupations that serviced cars and that utilized motorized vehicles for transportation and delivery.[17]

There are interesting insights to be gleaned from the shift from horses to automobiles. As with automation and artificial intelligence in our own day, it was a shift driven by new technology. But it wasn’t driven by technology alone, and its ultimate impact in many ways was by no means predictable at the time.

As one author has noted, what appears today as obvious – the transition from horses to cars – was in many respects far less than inevitable. As she points out, “the replacement of animal power took a particular form that was the result of cultural choices made about energy consumption at the turn of the century.”[18] The Progressive moment in the United States championed efficiency, sanitation, and safety improvements in cities, spurring not just the rapid adoption of automobiles that appeared to symbolize these benefits, but the rejection of horse-drawn travel that had problems in all three areas that urban dwellers understood all too well. In short, cultural values and a political movement contributed to the more rapid adoption of cars.

In a similar vein, it would be a mistake to assume that technology trends such as automation and the use of artificial intelligence will be driven by technology and economics alone. Individuals, companies, and even countries will make choices based on cultural values that will manifest themselves in everything from individual consumer preferences to broader political trends that lead to new laws and regulations. These may well diverge in different parts of the world.

As with automation and artificial intelligence in our own day, it was a shift driven by new technology. But it wasn’t driven by technology alone, and its ultimate impact in many ways was by no means predictable at the time.

Perhaps even more significant, technology transitions tend to have indirect but nonetheless sweeping implications that are difficult to predict at the outset. In many ways, this is because of the broader economic dynamics involved.

Take for example the impact of the automobile’s adoption on American agriculture. The resulting decline in the horse population cut demand for horse feed and contributed to an agricultural depression in the 1920s, which worsened even further during the Great Depression. A weak agricultural sector was a drag on the entire U.S. economy in the 1930s. In 1933, at the height of the Depression, the Bureau of the Census concluded that the transition from horses to cars was “one of the main contributing factors of the present economic situation” and had “affected the entire country.”[19] Until the economy recovered, the absence of horses on Broadway contributed to the decline of stock prices on Wall Street. But there were probably relatively few that focused on the connection in the heat of the moment.

Even less obvious initially was the wider variety of new industries the automobile helped create. A good example was the industry that grew quickly to enable consumer credit. By 1924, 75 percent of cars were paid for over time. Auto installment paper quickly represented over half the country’s retail installment credit. Then as now, cars typically were a family’s second most expensive possession even if they owned their home. People needed to borrow money to pay for them. “Installment credit and the automobile were both cause and consequence of each other’s success.”[20]

This leads to an interesting question. When New Yorkers saw the first automobile roll down the street in the nation’s financial capital, how many predicted that the new invention would lead to the creation of new jobs in this new part of the financial sector? The route from the combustion engine to consumer credit was indirect and unfolded over time, bolstered in no small part by other intervening inventions and business processes like Henry Ford’s assembly line, which made possible the cheaper, mass production of automobiles.

Similarly, the automobile transformed the world of advertising. Seen by passengers traveling in a car at a speed of 30 miles per hour or more, “a sign had to be grasped instantly or it wouldn’t be grasped at all,” giving birth to the creation of corporate logos that could be recognized immediately wherever they appeared.[21] Yet it’s doubtful that the early purchasers of automobiles imagined that they would contribute to new jobs that would line Madison Avenue.

All of this is sobering and encouraging at the same time, especially when it comes to the impact on future jobs. It’s sobering because there are so many factors that genuinely are unpredictable in a technology’s infancy. It’s encouraging because, in so many ways, the ability to predict the adverse impact on today’s jobs – positions we readily can identify – exceeds the ability to identify the new jobs and even industry sectors that new technology will help take flight. Put in this perspective, there is perhaps some room not just for optimism, but even a little faith, that human ingenuity will find new ways to work with and profit from the technology of tomorrow.

[1] “Last of Boro’s Fire Horses Retire; 205 Engine Motorized” The Brooklyn Eagle, 20 December 1922, p.2.

[2] Ibid.

[3] “1922: Waterboy, Danny Beg, and the Last Horse-Driven Engine of the New Work Fire Department,” The Hatching Cat: True and Unusual Animal Tales of Old New York, 24 January 2015. http://hatchingcatnyc.com/2015/01/24/last-horse-driven-engine-of-new-york-fire-department/.

[4] “Goodbye, Old Fire Horse; Goodbye!” Brooklyn Eagle, 20 December 1922, p 6.

[5] Augustine E. Costello, Our Firemen: A History of the New York Fire Department, Volunteer and Paid (New York: Knickerbocker Press, (1887) 1997), p. 94.

[6] Ibid., p. 424.

[7] Robert J. Gordon, The Rise and Fall of American Growth: The U.S. Standard of Living Since the Civil War (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016), p. 72.

[8] Ibid., p. 75.

[9] A 1,000-pound horse that does moderate work typically consumes 25,000 calories daily. http://www.dayvillesupply.com/hay-and-horse-feed/calorie-needs.html

[10] Ibid. at p. 62, quoting Ann Norton Greene, Horses at Work: Harnessing Power in Industrial America (Cambridge, Ma.: Harvard University Press, 2008), p. 167.

[11] Clay McShane and Joel Tarr, The Horse in the City: Living Machines in the Nineteenth Century (John Hopkins University Press, 2007), p. 38

[12] Ibid., p. 31

[13] Mike Wallace, Greater Gotham: A History of New York City from 1898 to 1919 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), p. 245.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid., p. 248.

[16] Ibid.

[17] McKinsey Global Institute, Jobs Lost, Jobs Gained: Workforce Transitions in a Time of Automation (December 2017), p. 43.

[18] Greene, p. x.

[19] Ibid, p. x.

[20] Lendol Calder, Financing the American Dream: A Cultural History of Consumer Credit, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1999), p. 184.

[21] John Steele Gordon, An Empire of Wealth: The Epic History of American Economic Power (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2004), p. 299-300.