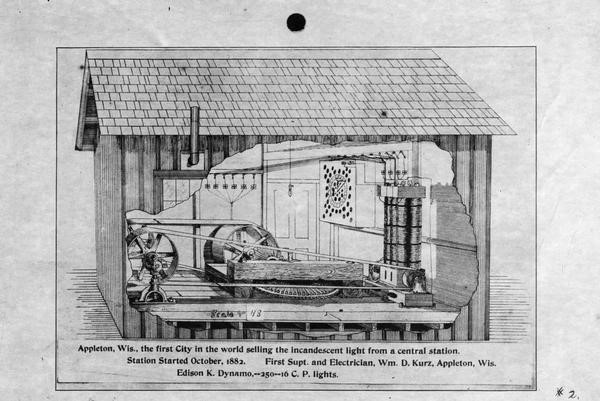

As the sun sank in the late-autumn sky in 1882, a steady stream of water flowed from the placid confines of Lake Winnebago down a well-worn path through the Wisconsin countryside. Rushing past sprawling farms, lonely stands of timber, and the waiting traps of fur traders, the Fox River plunged towards the town of Neenah and onward to Menasha. As the river made its way into the town of Appleton, gravity towed the water into the blades of the wooden waterwheel of the Vulcan Street Plant and the current struck the turbine, spun it to life, rotated a metal shaft connected to two Edison “K” dynamo generators and sparked “the miracle of the age”: electricity. [1]

The electrical current flowed into a pear-shaped bulb and slowly coaxed a thin hair of carbonized bamboo to life, releasing a steady glow inside the Vulcan plant’s wooden hut. It continued its journey, crackling along the loops of fresh copper wire and out into the cold, black night where, within minutes, the riverbank turned “bright as day” as the Appleton Paper and Pulp Company and its stately neighbor, the Hearthstone House, twinkled to life. [2]

As Appleton’s residents looked on in wonder, a wooden lean-to burst open as paper company executive Henry J. Rogers whooped in triumph. He and his partners had harnessed the Fox River’s turbulent waters, turning the Northeast Wisconsin night into day. It would be nine years before electricity would light up the nation’s White House.

The first electricity offered for sale anywhere in the world came from the Vulcan Street Plant. Wisconsin’s early firsts were followed by many more, including the West’s first hydroelectrically lit hotel, the Waverly House in 1883. The world’s first hydroelectrically lit college building, Lawrence University’s Ormsby Hall in 1886. And the nation’s first continuously successful commercial electric trolley system in 1886.

For all its success, hydropower and Rogers’ power company were not without issues. With no meters, customers were charged a flat monthly fee based on the number of installed electric lamps, so many people left their lights on through the night. Occasional power surges burned up pricey bulbs in minutes.

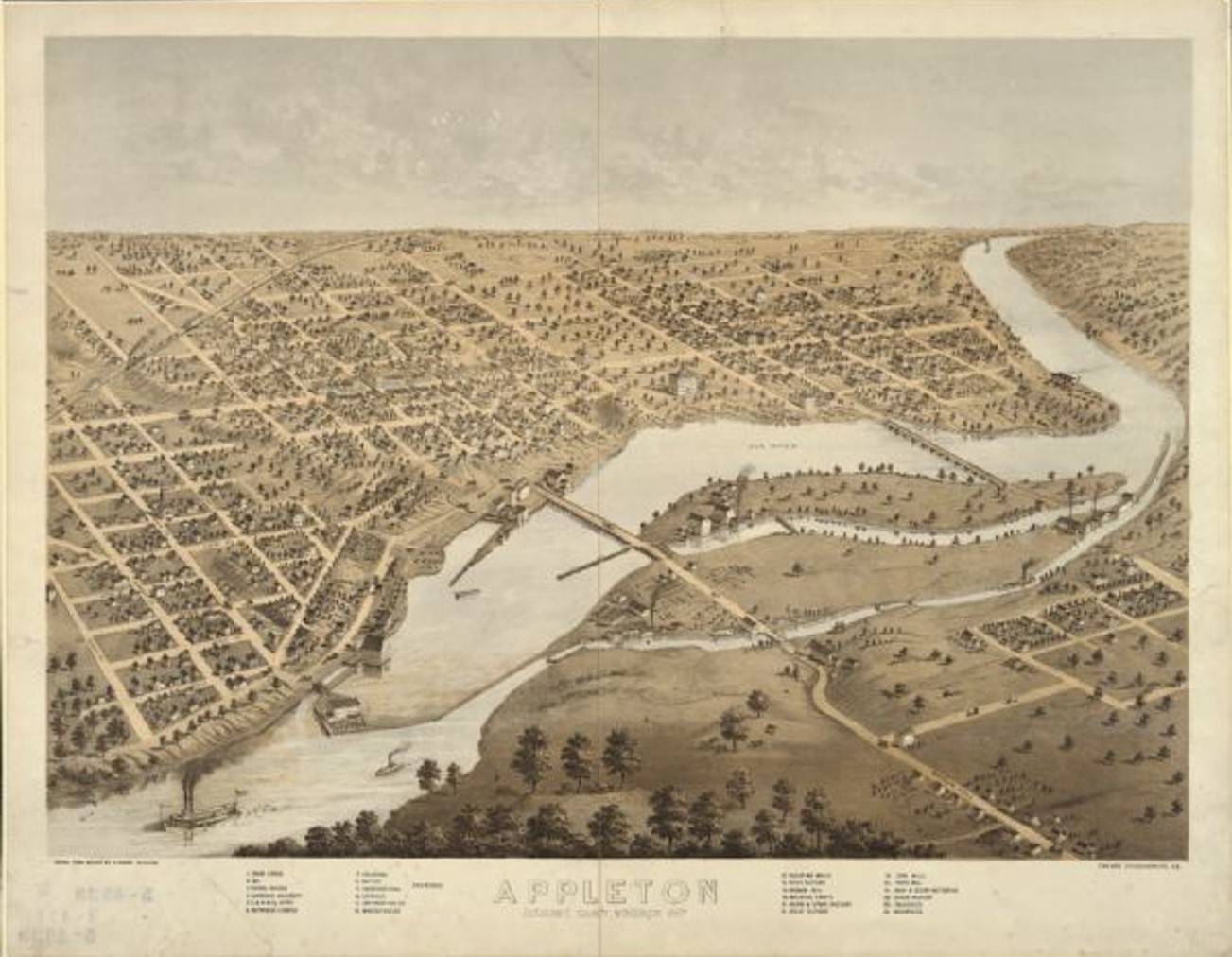

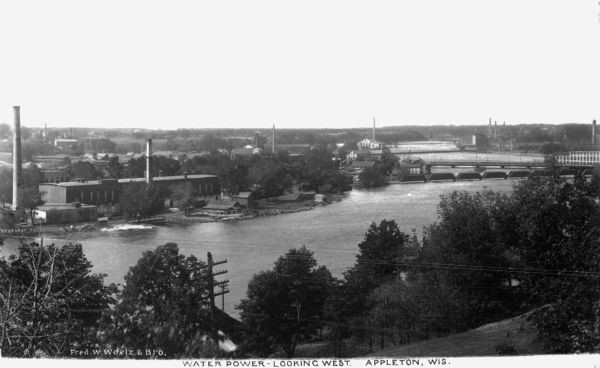

Wisconsin’s River of the Foxes, or Rivière aux Renards as French explorers Louis Jolliet and Jacques Marquette named the tributary in 1673, has long fueled development and opportunity in Northeast Wisconsin. Over the centuries, the river has provided a constant supply of water “as regular and uniform as the change of seasons.” [3] Fisheries, waterfowl, wild rice, forests, and water sustained the region’s indigenous people and early settlers for centuries before industrialists in the 1800s recognized the mechanical power of rushing water.

It would be nine years before electricity would light up

the nation’s White House.

By the early 1800s, the river became “a faithful servant of industry,” with settlers mastering its current to automate the milling of wheat into flour. In 1860, when the region’s wheat crop declined, Wisconsinites turned to the region’s forests and built a prosperous paper industry which yielded several notable corporations that endure today, like Kimberly-Clark and Hoberg Paper Company, the maker of Charmin.

Today, the Lower Fox is home to 24 paper and pulp mills producing five million tons of paper per year and employing around 50,000 people.

Winters are long and the days are short in Wisconsin. And short days in Rogers’ time meant shorter operating hours at his mill. He knew that by lighting and heating the Appleton Paper and Pulp Company, he could extend operations and make more money. But oil and gas lamps were expensive and inefficient, so he went looking for a solution. And he found his answer on a fishing trip with friend H.E. Jacobs, an agent of Chicago’s Western Edison Light Company.

Jacobs informed Rogers that Thomas Edison – the “Wizard of Menlo Park” – had developed a long-lasting incandescent bulb in New Jersey that could replace gas and oil lamps with carbon filaments and strips of coiled copper wires. Edison had created a light bulb that could burn up to 1,200 hours and, he bragged, make “electricity so cheap that only the rich will burn candles.”

Rogers set out to adopt Edison’s invention and convinced local Wisconsin investors to form the Appleton Edison Electric Company. But while most imagined river power used for manufacturing, Rogers envisioned using it for electricity generation that would reach homes as well. While Edison was busy building the steam-powered Pearl Street Plant in New York, which would later light up Wall Street, Rogers and his investors drew up plans for a plant powered by the “unequalled water-power afforded by the Fox River.” [4] The founders decided to test the viability of hydro-electric lighting in their own homes and mills that lined the river.

electricity so cheap that only the rich will burn candles

On September 30, 1882, Rogers ran electricity to his mill, his own home on the bluff above, and Kimberly & Clark’s Vulcan Paper Mill located nearby. On November 25, the Vulcan Hydroelectric Central Station opened, running 250 Edison electric lights and lit the blast furnace, a flax mill, a woolen mill, a paper mill and the residences of the power company’s investors A.L. and H.D. Smith.

Appleton’s electric lights inspired wonder in those early days, drawing people for miles to see the glowing “buttons.” Rogers himself was smitten with his success. In a letter to his investors he wrote, “Gentlemen, I have used 50 lamps in my residence and have used them about 60 days. I am pleased with them beyond expression and do not see how they can be improved upon. No heat, no smoke, no vitiated air, and the light steady and pleasant in every way and more economical than gas and quite as reliable.”

At a time when almost everything was made of wood, the bare copper distribution wires were a dangerous fire hazard. Edison’s electric design also had limitations because it failed to deliver electricity at distances greater than one mile. It would take Nikola Tesla’s designs in the 1890s to successfully transmit electricity at greater distances. Tesla’s first commercial attempt was his Niagara Falls plant, which brought power to Buffalo, New York, 26 miles away.

Appleton Edison Electric Company could not properly regulate and monitor its service and eventually suffered financial ruin. Yet despite the difficulties, Rogers and his investors conceived of an important renewable energy source that more than 130 years later provides 25 percent of global electricity generation. At a time when the world is grappling with climate change and looking to lower carbon, the hydropower that Rogers sparked in 1882 has never been more important.

At a time when the world is grappling with climate change and looking to lower carbon, the hydropower that Rogers sparked in 1882 has never been more important.

But Henry Rogers’ innovation on the Fox River stands for even more than that. During the last several decades, the shrinking of the Midwest’s once-powerful industrial sector has hit the Great Lakes region hard. Innovation in America has been fueled by advances in digital technology and increases in wealth more typically concentrated in the country’s largest cities that line the two coasts. Rogers’ example reminds us that it wasn’t always this way. And it doesn’t need to remain this way. Talented people live across the country in communities large and small, from the coasts to the plains. They deserve a better opportunity to pursue a brighter future in the towns where they grow up. What we need is new approaches that will better spread to every part of the country the opportunity for technology to create a brighter future for everyone.

As in Rogers’ day, it takes a few pioneers with vision to show the way. Over the past decade, no one has done more to highlight the opportunity for a new generation of innovation in the Midwest than Steve Case, the founder of America Online, or AOL. He has used his “Rise of the Rest” bus trips to highlight the opportunities for entrepreneurs in cities and towns across the center of the country. And he has supported his words with financial backing from his Revolution LLC investment fund.

Increasingly Case’s message is reaching a new generation of innovators and entrepreneurs working across Middle America. They include the exciting work of two individuals, Joe Kirgues and Troy Vosseller, the co-founders of gener8tor, a nationally ranked accelerator based in Wisconsin that invests in high-growth startups, including in Appleton, Green Bay, and the rest of the Fox River Valley. Microsoft has had the opportunity to serve as a sponsor of gener8tor’s gBETA free accelerator for early-stage companies with local roots in Northeast Wisconsin.

Case’s and gener8tor’s work is part of what has inspired us to focus on what Microsoft can do to better support opportunities for technology innovation in every corner of the country. As we’ve rolled up our sleeves and engaged with local communities, we’re starting to learn more about what’s needed to bring innovation back to smaller cities and towns in the United States. And this has directed some of our work in new directions.

We live in a time when it’s easy to talk about a divided America. On some days the divide is characterized by partisanship and a division between our political parties. On other days the news is characterized by racial or economic divides. But there’s another divide that deserves our attention: it’s the technology divide that impacts too much of the United States.

One simple but powerful way to measure access to technology today is whether people have access to broadband. And in the United States today, 23.4 million people in rural America do not. It’s not even a question of affordability. There simply is no broadband service they can buy.

Broadband is no longer just about watching YouTube videos or the latest hits on Netflix – although it’s worth remembering that as many in the nation discuss the latest episodes of Stranger Things, more than 20 million people live in communities that effectively have no access to it.

Broadband has become a necessity of life. It’s fundamental for a child’s ability to do homework after school. It’s essential for a veteran’s to access telemedicine services rather than spend four hours driving to a VA Hospital. It has become the future of farming with precision agriculture. And it’s vital for small businesses and their ability to expand their customer base and create new jobs.

As we look at the broad range of cloud services that our customers use to harness the power of Microsoft datacenters, it’s apparent that broadband has become the electricity of our age. Just as the country committed in the 20th century that every American would have access to electricity and long-distance telephones, the United States today needs to commit itself to ensuring that broadband coverage is available to everyone.

It’s apparent that broadband has become the electricity of our age.

As with electricity and telephony, this is an issue and opportunity not just for government but for companies and the private sector. That’s why we launched Microsoft’s Airband initiative in July. Its aim is to partner with telecommunications companies to bring broadband coverage to at least two million new Americans over the next five years. But its purpose is larger than that. It’s to advance new technology, spur the broader market and encourage policymakers across the country to take the additional steps needed to eliminate the rural broadband gap entirely by 2022. We believe this is an achievable, affordable, and even essential goal for the country.

But bringing innovation back to every part of the country will require more than broadband. It requires a broader range of investments in digital skills in schools, digital transformation for businesses, and digital support for non-profits.

That’s why we’ve launched Microsoft’s TechSpark program, which is partnering with six communities outside the countries’ large cities to invest in and learn more about how technology can better support economic growth in these parts of the country. It provides us with the opportunity to learn from local leaders in specific regions in Virginia, Texas, Wisconsin, North Dakota, Wyoming, and Washington State.

On October 20 in Green Bay we announced with the Packers the creation of TitletownTech. It will be part of a new building that the Packers will open in Titletown next year. It will include not only an accelerator for technology-focused start-ups, but a lab that will give traditional companies, including from the local paper industry, the opportunity for employees to work with mentors to develop new digital solutions to transform and grow their businesses. The Packers and Microsoft are each putting $5 million over the next five years into the effort, and equally important, it will be supported by the volunteer efforts of Microsoft employees who will serve as mentors.

At first blush it may seem an unusual match. But the Packers are more than a premier NFL franchise. They’re the heart and soul of an important community, an engine of economic growth, and a huge contributor to philanthropy. They’re building on their powerful legacy with a unique investment in TitleTown, a 45-acre development adjacent to Lambeau Field that is bringing to Green Bay and the Fox River Valley a new center for recreation, tourism, residences, businesses, and healthcare. And thanks to our partnership and the creation of TitletownTech, it will provide a new home for technology innovation as well.

As Mark Murphy, the President and CEO of the Packers, has recognized, Titletown and TitletownTech address an important local need. It’s a need common to Green Bay, the Fox River Valley, and many other parts of the center of the country. In recent decades many young people have grown up, gone off to college, and then moved to other parts of the country, many times to the coasts. As Mark has noted, TitleTown and TitletownTech will not only help offer new opportunities to retain local talent, but attract new people to the area. As Ed Policy, the Packers Vice President and General Counsel, said recently, TitletownTech adds to what is now a comprehensive approach for Titletown – a place where people will live, work, play, visit, and now create as well. It’s a powerful combination.

We believe that TitletownTech will add an exciting new element to important innovations that are already taking root in Northeast Wisconsin. We hope it will also provide new learning that we can help spread to other parts of the country.

Cutting-edge innovation took root in the center of America almost a decade before it reached the premier building in the nation’s capital. That’s our past. And it can be part of our future as well.

In an interesting way, this is an opportunity to build on the inspiration and legacy created by Henry Rogers. He lit his home in a small town with hydroelectric power nine years before electricity powered lightbulbs in the White House. Imagine that. Cutting-edge innovation took root in the center of America almost a decade before it reached the premier building in the nation’s capital. That’s our past. And it can be part of our future as well.

Today in Technology is a series that highlights important technology developments from the past and discusses the insights they offer for the tech trends and issues of our own day.

[1] “Milestones: Vulcan Street Plant, 1882 – Engineering and Technology History Wiki,” accessed October 15, 2017, http://ethw.org/Milestones:Vulcan_Street_Plant,_1882.

[2] Kellogg, pg. 192

[3] Ibid, pg. 46

[4] A.J. Reid, The Resources and Manufacturing Capacity of the Lower Fox River Valley, in Summers, Consuming Nature, p. 45.