The May 23-26 European Parliament elections are fast approaching, and in the run up to these critical elections, many questions have been raised over security, foreign election interference and the role of technology in the process. Canada’s cyber security agency recently found that half of all developed countries holding elections in 2018 reported some form of cyber threat to their democratic processes, a threefold increase since 2015.

Such threats have created concerns around the targeting of digital components of elections, as detailed in previous Microsoft blogs. As a result, some governments have scaled back the use of technology in their election systems, even though many of the high-profile digital attacks have focused on the spread of disinformation on social media rather than targeting the actual election infrastructure.

Governments can respond to election-related cyber threats in a way that embraces technology and creates a system which commands public trust. Estonia implemented the EU’s first country-wide internet voting (i-voting) system in 2005. Two years later, a denial-of-service cyberattack targeted both private and public sector websites. It happened after a Soviet-era statue was relocated, and hit media outlets, banks and government bodies. Estonians could not use cash machines or online banking. Newspapers and broadcasters were unable to reach their audiences.

The scare could have prompted Estonia to roll back on its electronic innovations, but instead it chose to, apply lessons learned, lean into technology, opting for good cybersecurity and technological advancement as the best defense.

Estonia’s i-voting system is attracting hundreds of foreign delegations coming to Tallinn to see it in practice. The Estonian government is showcasing the system as a model for other governments on how online voting can be done. Estonia also demonstrated leadership by co-chairing the group that prepared the Compendium on the Cybersecurity of Election technology that set baseline for the European Commission’s package on Securing Free and Fair European Elections.

Tarvi Martens, Chairman of the Estonian Electronic Voting Committee, spoke to Microsoft about the benefits of their system, challenges for the future, and advice to other EU countries. The analysis and opinions expressed herein are solely those of the interviewee.

When and why did Estonia introduce internet voting?

The government began the legislative process in 2001 and introduced the new voting system in 2005. By 2002, Estonia had also introduced an ID card system and by 2005 almost 80% of the electorate had this ID card. At the time, Estonians were saying they did everything with their computer – their banking, taxes, signing documents – and asked: “why not voting?”

Could you talk us through the process of casting a vote online?

The process is actually pretty simple. The voter goes to the elections webpage and downloads an application to cast their vote. Next, the voter identifies his or herself using their ID card inserted into smart card reader or their mobile phone. Once the voter is authenticated with a PIN code it would say “welcome, here is your candidate list.” The voter can then cast their vote for their preferred candidate. The whole process takes around 40 seconds – unless you take more time to decide which candidate to vote for!

How is the internet voting process secured?

Securing the internet voting process is similar to the way we secure other high importance information systems such as banking and critical infrastructure. The trick is to guarantee the secrecy of the votes.

To do this, the ballots are immediately encrypted on the computer when you vote, and they are decrypted centrally by the election commission only once they are anonymized. There is no tag of who voted how, so that’s how we can maintain secrecy and privacy. Our system is like using a double envelope system for a ballot, where we can only count – or decrypt – anonymous votes.

The voter can also check whether his or her vote has arrived at the election commission server properly using a secondary device. After the voter casts their vote online, they can then use an application on their smartphone to scan a QR code from the computer. The QR code enables your device to communicate to the state election servers to show the voter how he or she voted without compromising the privacy of the vote cast.

Finally, there are additional mechanisms to preserve the integrity of the electronic ballot box. Votes are registered with a third party –an accredited trust service provider who issues a timestamp. These timestamps, collected from the trust service provider logs, are later compared with the electronic ballot box to make sure they coincide. That ensures that the administrator of the electronic ballot box cannot delete votes at random or produce extra votes.

What about people’s sense of the integrity of the election? Do people feel safe in Estonia voting on the internet?

Trust in the system is rising continuously. Before this year we had three elections with around 31% of people voting on the internet. During the last elections in March we had a significant increase to 44% of voters using the online system. That is the highest proportion yet of people using i-voting in Estonia.

The further away a voter lives, the more likely they are to vote from home. Also, if you are between the ages of 25 and 45, you are more likely to vote online because young people are more familiar with technology.

Who benefits most from an i-voting system?

There is a correlation between i-voting and how far a voter lives from a polling station. The further away a voter lives, the more likely they are to vote from home. Also, if you are between the ages of 25 and 45, you are more likely to vote online because young people are more familiar with technology. I-voting is also helpful for people with disabilities. While Estonia has long supported making the voting process accessible for people with disabilities through paper-based voting from home, they can now also vote online. And of course, i-voting is pretty much the only option for people travelling or residing out of the country for a longer period.

What about cost? Is an i-voting system cheaper than a paper voting system?

Initially, there are additional costs. For example, as we introduced this additional voting method, we still had to maintain the paper-based voting infrastructure. But once it is set up, it is significantly cheaper. After the fourth election using i-voting, we calculated the costs and found out that the electronic vote is about half the price of a paper vote.

Is the i-voting process easier to manage?

Yes, because it is centralized. We can do things very fast and conveniently.

Have many government delegations come to Estonia to learn about your system?

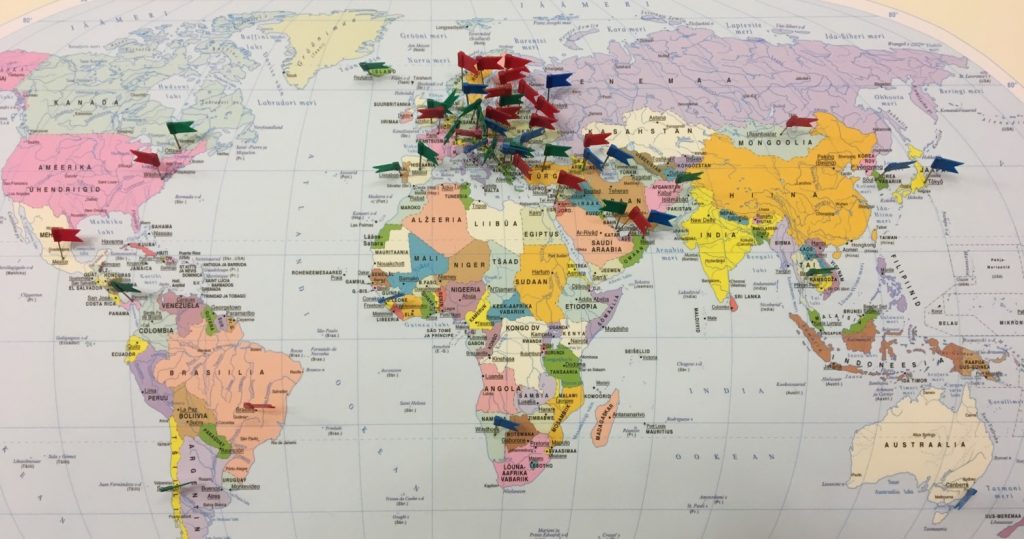

There is a map of the world in our office, and we have put a pin in every country which has sent a delegation to visit. It’s hard to find a country without a pin in it! During the last election in March, we had over 100 foreign officials visiting Estonia from 30 countries around the world.

Among these government delegations, what are the most common concerns about online voting?

We see a general fear of the unknown. It takes two things to introduce internet voting in a country: First, a kind of ID card or mobile ID – an electronic identity infrastructure.

Second, it takes political will. Politicians are most interested in getting re-elected. They don’t want to mess with the electoral system and the average politician doesn’t know much about the internet and security, so they would say, “let’s not mess with that.” So, it takes courage to start the process.

What advice would you give other EU countries regarding the adoption of technology?

You just have to make a start, at least at a research level. Introducing a new voting method is a wide, society-embracing topic and might take long time. Just have in mind that at some point internet voting will be inevitable.

Has there been interference or targeting of the online platforms in Estonia?

The elections have never been targeted specifically. The cyberattack of 2007 thankfully happened two months after the elections. That attack was regarded as the first countrywide cyberattack targeting all the sectors, both private sector and public sector. But I think our information security was high and we handled it well. There was one and a half days of disturbance and then it was contained.

What did you learn from that experience?

It was a very good exercise. Now we can teach others how to defend against those kinds of attacks. Those attacks and our ability to counter them led to the opening of the NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence in Estonia which has been one of the preeminent organizations leading the world’s discussions on the application of international law in cyberspace.

Are there any more technological innovations that you’re planning to implement in future elections?

There have been discussions about introducing voting on mobile devices, but we currently use the mobile device to verify the computer-based vote. If we move to voting from mobile devices, what do we use as second device for verification of the correct behavior of the mobile device? That’s the main challenge that we are thinking through right now. We are analyzing this, and after the European Parliament elections we will systematically research this issue. Overall, I would say that so far, we are proud of what we have achieved.