Today, Microsoft’s Digital Threat Analysis Center (DTAC) is attributing a recent influence operation targeting the satirical French magazine Charlie Hebdo to an Iranian nation-state actor. Microsoft calls this actor NEPTUNIUM, which has also been identified by the U.S. Department of Justice as Emennet Pasargad.

In early January, a previously unheard-of online group calling itself “Holy Souls,” which we can now identify as NEPTUNIUM, claimed that it had obtained the personal information of more than 200,000 Charlie Hebdo customers after “gain[ing] access to a database.” As proof, Holy Souls released a sample of the data, which included a spreadsheet detailing the full names, telephone numbers, and home and email addresses of accounts that had subscribed to, or purchased merchandise from, the publication. This information, obtained by the Iranian actor, could put the magazine’s subscribers at risk of online or physical targeting by extremist organizations.

We believe this attack is a response by the Iranian government to a cartoon contest conducted by Charlie Hebdo. One month before Holy Souls conducted its attack, the magazine announced it would be holding an international competition for cartoons “ridiculing” Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei. The issue featuring the winning cartoons was to be published in early January, timed to coincide with the eighth anniversary of an attack by two al-Qa’ida in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP)-inspired assailants on the magazine’s offices.

Holy Souls advertised the cache of data for sale for 20 BTC (equal to roughly $340,000 at the time). The release of the full cache of stolen data – assuming the hackers actually have the data they claim to possess – would essentially constitute the mass doxing of the readership of a publication that has already been subject to extremist threats (2020) and deadly terror attacks (2015). Lest the allegedly stolen customer data be dismissed as fabricated, French paper of record Le Monde was able to verify “with multiple victims of this leak” the veracity of the sample document published by Holy Souls.

After Holy Souls posted the sample data on YouTube and multiple hacker forums, the leak was amplified by a concerted operation across several social media platforms. This amplification effort made use of a particular set of influence tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs) DTAC has witnessed before in Iranian hack-and-leak influence operations.

The attack coincided with criticism of the cartoons from the Iranian government. On January 4, Iranian Foreign Minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian tweeted: “The insulting and discourteous action of the French publication […] against the religious and political-spiritual authority will not be […] left without a response.” That same day, the Iranian Foreign Ministry summoned the French Ambassador to Iran over Charlie Hebdo’s “insult.” On January 5, Iran shuttered the French Institute for Research in Iran in what the Iranian Foreign Ministry described as a “first step,” and said it would “seriously pursue the case and take the required measures.”

There are several elements of the attack that resemble previous attacks conducted by Iranian nation-state actors including:

- A hacktivist persona claiming credit for the cyberattack

- Claims of a successful website defacement

- Leaking of private data online

- The use of inauthentic social media “sockpuppet” personas – social media accounts using fictitious or stolen identities to obfuscate the account’s real owner for the purpose of deception – claiming to be from the country that the hack targeted to promote the cyberattack using language with errors obvious to native speakers

- Impersonation of authoritative sources

- Contacting news media organizations

While the attribution we’re making today is based on a larger set of intelligence available to Microsoft’s DTAC team, the pattern seen here is typical of Iranian state-sponsored operations. These patterns have also been identified by the FBI’s October 2022 Private Industry Notification (PIN) as being used by Iran-linked actors to run cyber-enabled influence operations.

The campaign targeting Charlie Hebdo made use of dozens of French-language sockpuppet accounts to amplify the campaign and distribute antagonistic messaging. On January 4, the accounts, many of which have low follower and following counts and were recently created, began posting criticisms of the Khamenei cartoons on Twitter. Crucially, before there had been any substantial reporting on the purported cyberattack, these accounts posted identical screenshots of a defaced website that included the French-language message: “Charlie Hebdo a été piraté” (“Charlie Hebdo was hacked”).

A few hours after the sockpuppets began tweeting, they were joined by at least two social media accounts impersonating French authority figures – one imitating a tech executive and the other a Charlie Hebdo editor. These accounts – both created in December 2022 and with low follower counts – then began posting screenshots of the leaked Charlie Hebdo customer data from Holy Souls. The accounts have since been suspended by Twitter.

The use of such sockpuppet accounts has been observed in other Iran-linked operations including an attack claimed by Atlas Group, a partner of Hackers of Savior, which was attributed by the FBI to Iran in 2022. During the 2022 World Cup, Atlas Group claimed to have “penetrated into the infrasrtructures” [sic] and defaced an Israeli sports website. On Twitter, Hebrew-language sockpuppet accounts and an impersonation of a sports reporter from a popular Israeli news channel amplified the attack. The fake reporter account posted that after traveling to Qatar, he had concluded that Israelis should “not travel to Arab countries.”

Along with screenshots of the leaked data, the sockpuppet accounts posted taunting messages in French including: “For me, the next subject of Charlie’s cartoons should be French cybersecurity experts.” These same accounts were also seen attempting to boost the news of the alleged hack by responding in tweets to publications and journalists, including Jordanian daily al-Dustour, Algeria’s Echorouk and Le Figaro reporter Georges Malbrunot. Other sockpuppet accounts claimed that Charlie Hebdo was working on behalf of the French government and said that the latter was seeking to divert the public’s attention from labor stoppages.

According to the FBI, one goal of Iranian influence operations is to “undermine public confidence in the security of the victim’s network and data, as well as embarrass victim companies and targeted countries.” Indeed, the messaging in the attack targeting Charlie Hebdo resembles that of other Iran-linked campaigns, such as those claimed by the Hackers of Savior, an Iran-affiliated persona that, in April 2022, claimed to infiltrate the cyber infrastructure of major Israeli databases and published a message warning Israelis, “Do not trust to your governmental centers.”

Whatever one may think of Charlie Hebdo’s editorial choices, the release of personally identifiable information about tens of thousands of its customers constitutes a grave threat. This was underlined on January 10 in a warning of “revenge” against the publication from Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps commander Hossein Salami, who pointed to the example of author Salman Rushdie, who was stabbed in 2022. Added Salami, “Rushdie won’t be coming back.”

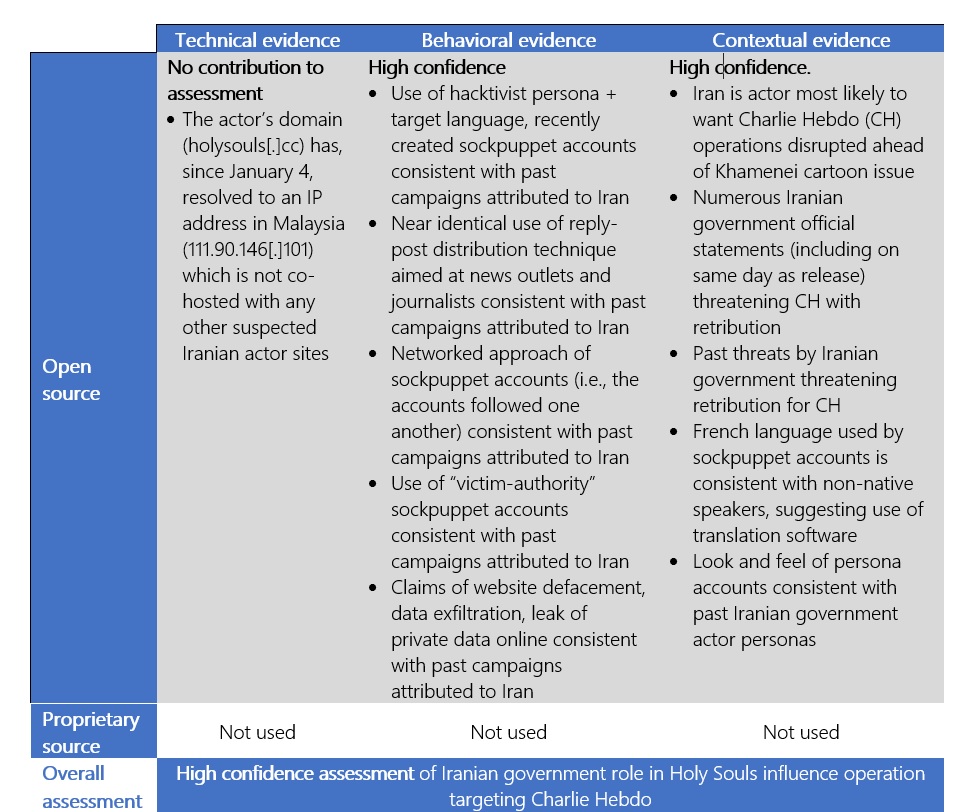

The attribution we’re making today is based upon the DTAC Framework for Attribution.

Microsoft invests in tracking and sharing information on nation-state influence operations so that customers and democracies around the world can protect themselves from attacks like the one against Charlie Hebdo. We will continue to release intelligence like this when we see similar operations from government and criminal groups around the world.

Influence Operation Attribution Matrix[1]

[1] Adapted from Pamment, James, and Victoria Smith. “Attributing Information Influence Operations: Identifying Those Responsible for Malicious Behaviour Online.” (2022). https://stratcomcoe.org/pdfjs/?file=/publications/download/Nato-Attributing-Information-Influence-Operations-DIGITAL-v4.pdf