Editor’s Note: On July 20, Kemba Walden, Assistant General Counsel, Digital Crimes Unit, Microsoft, testified before the House Energy and Commerce Committee’s Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations for a hearing “Stopping Digital Thieves: The Growing Threat of Ransomware.” Read Kemba Walden’s written testimony below and watch the hearing here.

Chairman DeGette, Ranking Member Griffith and Members of the Subcommittee, my name is Kemba Walden, and I am an Assistant General Counsel in Microsoft’s Digital Crimes Unit (“DCU”), where I lead our Ransomware Analysis and Disruption Program. I am also the co-chair of the Disruption working group of the Institute for Security and Technology (IST) Ransomware Task Force, which brings together experts across industries to combat the threat of ransomware.[1] Prior to Microsoft, I spent a decade in government service at the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. At DHS, I held several attorney roles, specifically as the lead attorney for the DHS representative to the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States and then as a cybersecurity attorney for the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, and its predecessor. I want to thank you for the opportunity to discuss ransomware attacks and illustrate why increased and meaningful information-sharing and public private partnerships are critical to combatting this latest virulent example of costly cybercrime.

I’m also pleased to share information about how Microsoft is combatting ransomware. We believe the best strategy to decrease ransomware attacks is through targeted disruption campaigns along with increased cyber security hygiene. I will close by highlighting several key opportunities for more effective disruption of this cybercrime, opportunities to raise the collective security of public sector and private sector organizations, and the importance of partnerships.

Ransomware attacks pose an increased danger to all Americans as critical infrastructure owners and operators, small and medium businesses, and state and local governments are targeted by sophisticated criminal enterprises and nation-state proxies, operated by distinct criminal organizations. A sustainable and successful effort against this threat will thus require a whole-of –government strategy executed in close partnership with the private sector.

I. Microsoft’s Approach to Cybercrime

Microsoft plays offense against online threats. Working through robust partnerships, we strive to take down criminal infrastructure and pursue both financially motivated and nation state supported cybercriminals. This work helps us to protect our customers and to improve the safety of the global internet community so that all users – enterprises, consumers, and governments – can trust the technology and online services on which we rely for commerce and communication. The Microsoft Digital Crimes Unit (DCU) is an international team of technical, legal, and business experts that has been fighting cybercrime to protect victims since 2008. We use our expertise and unique view into online criminal networks to act. We share insights internally that translate to security product features, we uncover evidence so that we can make criminal referrals to appropriate law enforcement throughout the world, and we take legal action to disrupt malicious activity.

As part of the DCU, Microsoft’s new Ransomware Analysis and Disruption Program, which we launched in 2020, strives to make ransomware less profitable and more difficult to deploy by disrupting infrastructure and payment systems that enable ransomware attacks and by preventing criminals from using Microsoft products and services to attack our customers. The program is based on Microsoft’s decade-long experience and history of success driving a sustained fight against other types of cybercrime.

In addition to partnering with law enforcement to disrupt cybercriminals involved in ransomware attacks, such as the recent disruption of the payment system of the cybercriminals that attacked Colonial Pipeline, Microsoft also uses our expertise to inform cybercrime legislation and global cooperation that advances the fight against cybercrime. We provided substantial support to IST and participated in all four working groups of the Ransomware Task Force. I personally co-chaired the Task Force’s Disruption working group. My colleagues and I are also active participants in the World Economic Forum’s Partnership Against Cybercrime, focused on global policy efforts to combat ransomware.

Through Microsoft’s observations of ransomware deployment and attacks, our active collaboration with the U.S. Government to date, and Microsoft’s thought leadership in the global discussion on policy and operational opportunities to counter ransomware, I will next address opportunities for more effective disruption of this cybercrime, opportunities to raise the collective security of public sector and private sector organizations, and the importance of partnerships.

II. Defining Ransomware

A. What is a Ransomware Attack?

Ransomware is a specific kind of malicious software or “malware” used by cybercriminals to render data or systems inaccessible for the purposes of extortion – i.e., ransom. In a standard ransomware attack the cybercriminal achieves unauthorized access to a victim’s network, installs the ransomware, usually in locations with sensitive data or business critical systems, and then executes the program, locking files on that network, making them inaccessible to the victim until a ransom is paid. Usually, the ransom demand is for payment in the form of cryptocurrency – such as Bitcoin. Increasingly, attackers also steal sensitive data before deploying the actual ransomware in what is known as a double extortion ransomware attack. The theft of data compels the victim to engage in negotiations and raises the potential reputational, financial, and legal costs of not paying the ransom as the attackers will not only leave the victim’s data locked, but also leak sensitive information that could include confidential business data or personally identifiable information.

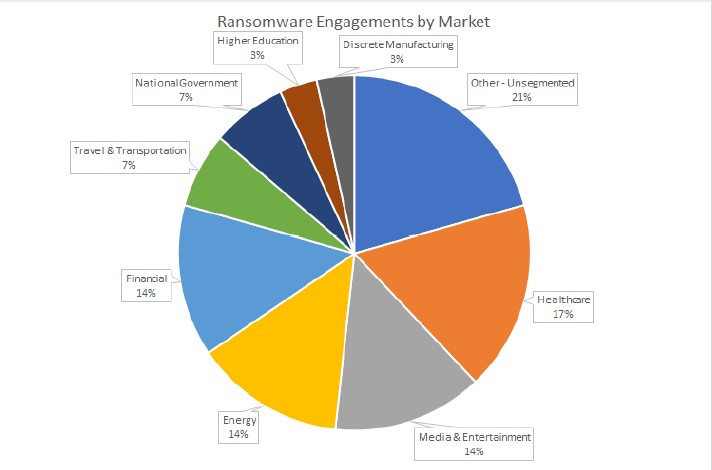

Recent, high-profile incidents such as those involving the Colonial Pipeline, JBS Foods, and Kaseya ransomware attacks drew considerable public attention and illustrate the extent of the threat and the significant, multimillion dollar consequences of ransomware. However, based on Microsoft’s data, ransomware is not limited to high-profile incidents. It is ubiquitous and pervasive, impacting wide swathes of our economy, from the biggest to the smallest players. Our data shows that the energy sector represents one of the most targeted sectors, along with the financial, healthcare, and entertainment sectors. And despite continued promises by some cybercriminals not to attack hospitals or healthcare companies during the global pandemic, Microsoft has observed that healthcare remains the number one target of ransomware.

B. How does a ransomware attack work?

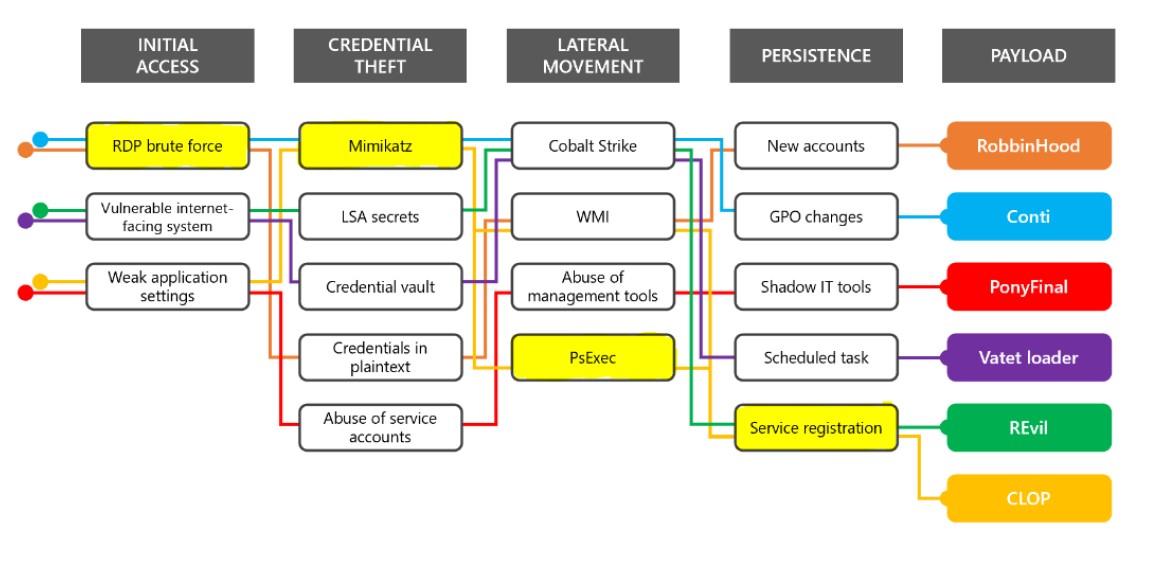

The image below depicts the basic steps that typically take place before a cybercriminal installs the malicious ransomware on a victim’s network. First, cybercriminals will gain access to the victim’s network through phishing, a stolen password, or through an unpatched software vulnerability. Then, the cybercriminals will seek to move laterally within the network to obtain higher level privileges, such as those held by the victim’s IT Administrator, to access the entire network. Cybercriminals will then conduct reconnaissance within the victim’s network, looking for critical systems and sensitive data, in some cases stealing this data, to facilitate an effective ransom demand. Finally, the cybercriminals will leverage this information to install the ransomware on the network that will lock the victim’s files until the ransom is paid.

C. How do cybercriminals ransom targets?

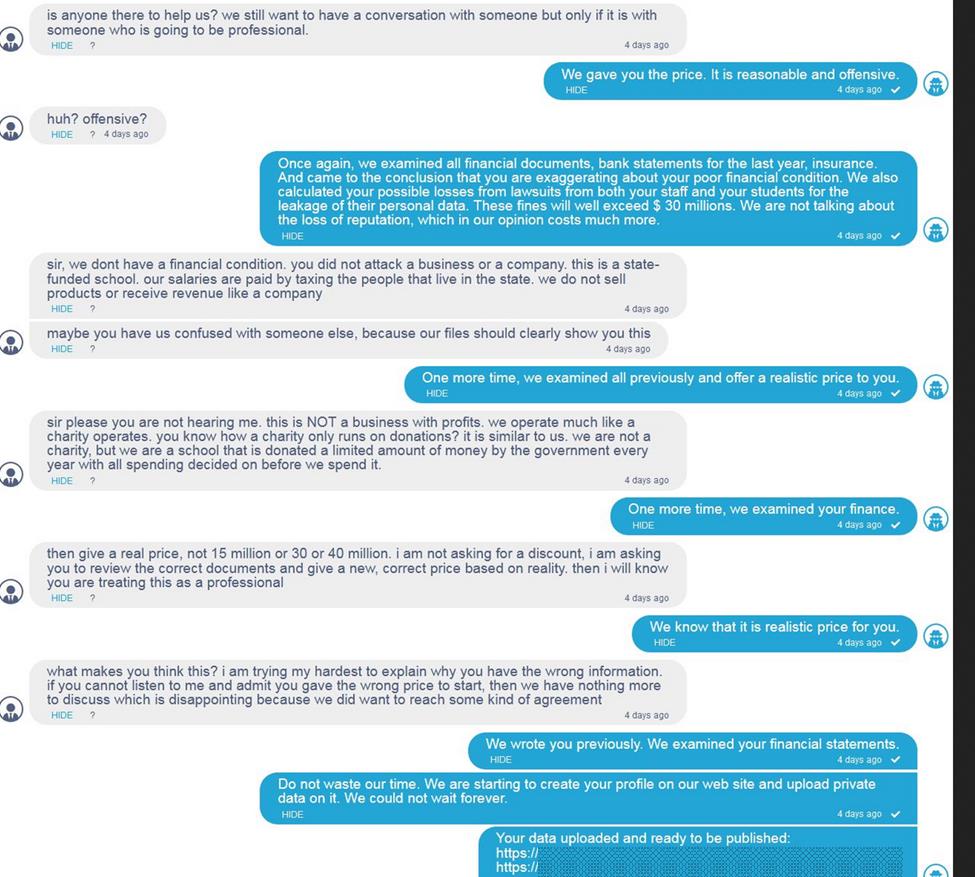

Ransomware has effectively evolved into a highly lucrative business model, with an accompanying advanced intelligence collection aspect. Criminal actors collect and perform research and analyze their intelligence to identify an optimal dollar amount for their ransom demand. Once criminal actors break into a network, they may access and study their target’s financial documents and insurance policies to better inform their eventual ransom demand and negotiating position. They may even research the penalties associated with that organization’s local breach laws. The actors will then extort money from their victims, not only in exchange for unlocking their systems, but in some cases to prevent public disclosure of the victim’s stolen data. Leveraging the significant intelligence they can gather on victim companies, the criminal actor will then launch their attack, identifying what they regard as an “appropriate” ransom amount.

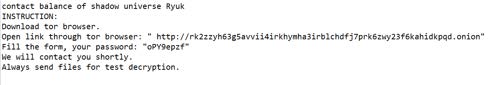

Once the criminal actor installs the ransomware and uses it to lock the victim’s system, the victim will have access only to a ransom note. The ransom note provides instructions to the victim on how to communicate with the criminal actor. In the example below, the criminal used the ransomware strain known as Ryuk – one of many popular ransomware software packages in wide-spread use today. The criminal directs the victim to access the deep web using the tor browser, a special means for accessing the deep web. At this point, the victim can open communications with the criminal to negotiate the ransom or pay it.

The negotiation process and back-and-forth communications are often surreal and disturbing in the nonchalance with which some criminal actors offer to “help” companies recover from the very attack they have orchestrated. The example below depicts a negotiation chat with a public school district in which the criminals attempt to extort cash in exchange for a key to unlock the ransomware deployed on its network. The interaction demonstrates the research performed by the criminal in advance of the negotiation, as the criminal actor explained that they had

“examined all financial documents, bank statements for the last year, insurance. And came to the conclusion that you are exaggerating about poor financial condition. We also calculated your possible losses from lawsuits from both your staff and your students for the leakage of their personal data. These fines will exceed $30 million. We are not talking about the loss of reputation, which in our opinion costs more.”[2]

D. What barriers to entry exist to executing a ransomware attack?

Very few. A cybercriminal does not need specialized computer coding skills to profit from ransomware. The only cybercriminal in the entire ransomware lifecycle who requires specialized code development skills is the originator who develops the malicious software in the first place. There are hundreds, if not thousands of different ransomware variants, such as Ryuk, Darkside, REvil, Maze, and Conti. Attacks are often misleadingly named after the malicious software that was installed on a victim’s network though the cybercriminals involved in the attack may not have any link to creator of that particular ransomware. A single cybercriminal may use any number of ransomware variants in conjunction with other tools to attack victim networks.

Increasingly, cybercriminals who use ransomware have moved to a “Ransomware as a Service” business model that is driven by human intelligence and research. This has further decreased the barriers to entry for any cybercriminal. Ransomware as a Service is a “modular” business model where individuals with limited technical skills can leverage the malware developed by others to conduct their own attacks.

Developers or managers will use hacker forums to recruit affiliate hackers. For example, as Bleeping Computer reported last fall, REvil developers used hacker forums to actively recruit affiliate hackers. To facilitate the business aspect of the relationship, developers create and run ransomware and payment sites with affiliates who hack businesses and lock their devices. Developers typically get 20-30% of any ensuing ransom, with affiliates receiving 70-80%. This is effectively a crime syndicate where each member is paid for a particular expertise.

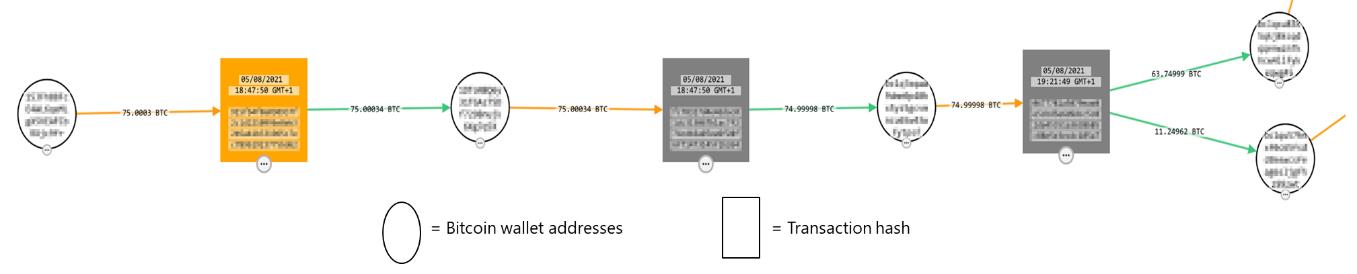

The below example, following the flow of cryptocurrency, shows how a criminal enterprise split its bitcoin (BTC) “earnings” such that approximately 25% of the earnings flowed to the developer/manager and 75% of the “earnings” flowed to the attacker.

Transaction hashes and wallet addresses intentionally blurred for publication

III. Opportunities for Disruption

Disruption of criminal activity does not eliminate the problem, but it raises the cost of committing the crime. Arrests and prosecution in cybercrime can be difficult, disrupting the infrastructure that is used by cybercriminals in ransomware attacks is therefore a key part of deterrence. In the case of ransomware, there are opportunities for both the public and private sector to focus on making the crime more difficult to commit (infrastructure disruption) and opportunities to focus on making the crime less profitable (payment disruption). The hope is that by shifting this balance, criminal actors will abandon this crime.

A. Disrupt the Infrastructure by targeting the criminal actor’s ability to communicate with the victim or publicly disclose stolen data.

There is not a “one size fits all” infrastructure disruption that will eliminate ransomware; rather, disruption will make it more difficult for the criminal actor to accomplish their goals, thereby raising the cost of committing this crime. Generally, infrastructure disruption focuses on removing the infrastructure such as websites, servers or email accounts that enable the criminal actor to negotiate the ransom with the victim and for publicly disclosing the victim’s sensitive data. Ransomware attacks often use the same infrastructure for multiple campaigns. Cybercriminals decide how to conduct their attack based on what security tools were present, whether the network had good cyber hygiene, and which data the cybercriminals wanted to exfiltrate from the network.

Although the new Ransomware as a Service business model relies on a variety of tools and ultimate choice of ransomware, all of them need to operate in a similar manner to effectively extract payment from victims. The infrastructure used is rather consistent. For example, every double extortion ransomware scheme needs a location to publicize the stolen data and an opportunity to establish communication with their victims to negotiate the terms of the ransom. This provides a disruption opportunity.

B. Disrupt the Payment Distribution System by targeting intermediaries that support the vulnerable elements of the system.

Disrupting the payment distribution system that supports this crime makes ransomware attacks less profitable. Improving our technical means and legal process for disrupting the infrastructure that supports payments earned through ransom will significantly impact the profitability (and thereby prevalence) of this crime. Because the payment distribution system and the intermediaries that support the money flow ranges across international borders, disrupting the payment distribution system will require a global strategy.

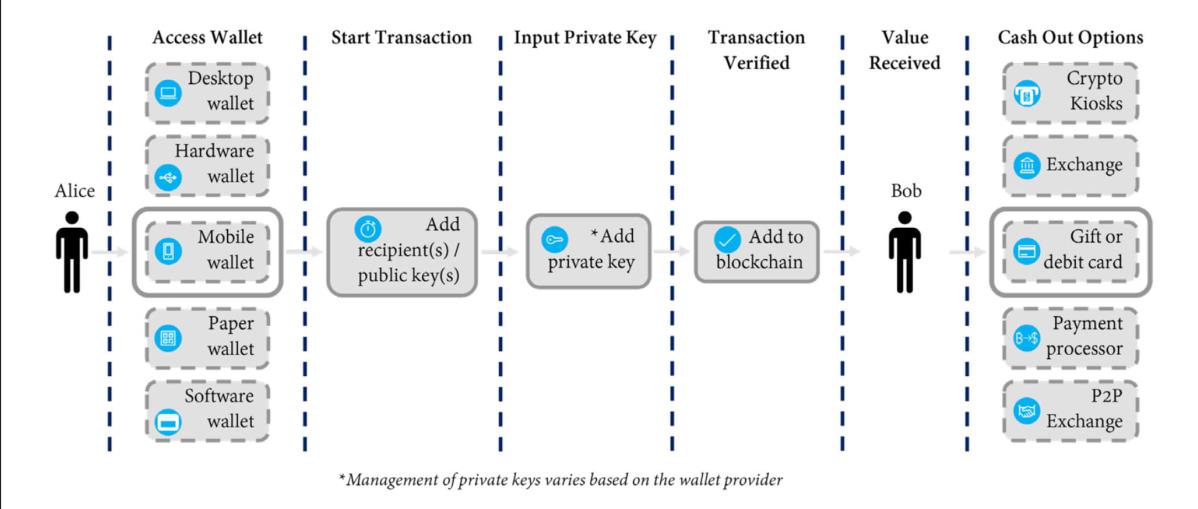

The infographic below demonstrates the flow of payment and opportunities for disruption: a victim (Alice) will obtain a wallet that is able to send cryptocurrency. There are several types of wallets – wallets that are held by a service provider on behalf of the owner (otherwise known as a “hot” wallet) or wallets that are in the sole custody of the owner and are not accessible by any other party (otherwise known as a “cold” wallet). Victims usually obtain “hot” wallets while criminals will often have both “hot” and “cold” wallets. There are a series of actions that are taken to send cryptocurrency in a pseudonymous manner ultimately resulting in its receipt by the criminal (Rob). Rob then has a variety of choices to convert his cryptocurrency payment into traditional fiat currency, like U.S. Dollars. Those options include going through a crypto kiosk (which is akin to an automated teller machine), using a crypto exchange, using a peer-to-peer exchange or using an over-the-counter trading desk. Other options include purchasing gift cards, gambling, or going through some other payment processor. It is these on-ramps (obtaining a “hot” wallet) and the off-ramps (exchanging digital currency into traditional currency) where the criminal actor is most vulnerable and the opportunity for disruption is greatest.

Regardless of where ransomware is deployed, typically the threat actors will demand payment via crypto currency. Though the underlying blockchain technology facilitates transparent cryptocurrency flows, the owners of wallets remain pseudonymous. To achieve this pseudonymity, first a threat actor must obtain a crypto wallet from a wallet services company and second, the threat actor will seek to cash out its crypto currency through some sort of platform. At its core, the criminal actor needs to append the blockchain with a transaction and ultimately find a way to cash out. Most stakeholders in this cryptocurrency system do not want their platforms used for nefarious purposes. Those that are compliant with U.S. laws are interested in partnering with the security community to make it more difficult for criminal actors to use

their platforms. However, some wallet service providers and crypto currency exchanges can exist in jurisdictions that are either unwilling or unable to effectively police these service providers. It’s these intermediaries that facilitate the flow of ill-gotten earnings from ransomware. The private sector through civil litigation, and the government through criminal seizure, regulatory enforcement, and international collaboration can take coordinated action to disrupt these weak points in the payment process. We applaud the U.S. Department of Justice’s formation of its internal Ransomware Task Force and recent operation to seize a wallet and crypto currency from the criminal gang that attacked Colonial Pipeline.

IV. Raising Awareness for Potential Victims.

Although disruption is important, preventing criminal actors from getting into networks in the first place and making organizations resilient to attacks are equally important. Potential victims, governments, organizations, and businesses of all sizes are at varying levels of preparedness maturity. Ensuring that all potential victims increase their security and resilience is key.

Cybercriminals who install ransomware use tried and true methods for access. Often, applying basic cybersecurity hygiene can prevent a cybercriminal’s ability to ransom a system. Consider, for example, the recent ransomware attack against EDGAR, the Securities and Exchange Commission’s Electronic Data Gathering, Analysis, and Retrieval system. Cybercriminals were able to access the network through an IT Administrator’s password that was compromised in an earlier breach.[3]

Microsoft recommends that the government produce clear useable guidance to address common points of confusion around ransomware attacks, clarifying what organizations should do first, next, and after that (1-2-3 style guidance). Although NIST has done an excellent job of addressing many aspects of these attacks, organizations still struggle with where to start (especially smaller organizations with limited staff and experience). Any government guidance should clearly state top security priorities, and why they are important. For example, a simple three step approach could be effective: (1) Make it harder to get in, (2) Limit the scope of damage and (3) Prepare for the worst.

Making it harder to get in. There are several basic cybersecurity hygiene steps that can be taken to make it much harder for attackers to gain access to the victim’s network. The most important of these steps is the use of multi-factor authentication. A study done at Microsoft estimates that more than 99% of all cyberattacks would have been prevented if multi-factor authentication were deployed. Multi-factor authentication is important to raising friction for entry but will take time to complete as part of a larger security journey. Other steps can be taken to identify and close off vulnerable entry points. Limiting the scope of damage forces the attackers to work harder to gain access to multiple business critical systems by establishing least privileged access and adopting Zero Trust Principles. These steps make it harder for an attacker who gets into a network to travel across the network in order to find valuable data to lock up. There are many resources that describe how to do this effectively, and simple free tools, like those from the Cyber Risk Institute, can help even small and medium size businesses do this work. Finally, encouraging potential victims to prepare for the worst is designed to minimize the monetary incentives for ransomware attackers by making it harder to access and disrupt systems and easier for victims to recover from an attack without paying the ransom.

The recently launched Stop Ransomware website hosted by DHS/CISA is a fantastic resource for explaining ransomware, providing a step by step guide to responding to a ransomware attack, and providing best practices for preparedness.

V. The importance of Public – Private Partnerships

Just as committing ransomware attacks requires collective effort, countering ransomware attacks needs the same focus and global coordination. As these attacks have evolved to more sophisticated enterprise-like operations involving multiple players, countering these efforts requires a multi-stakeholder approach. Each of us has an important role to play, with the foundation of our efforts being reliable information and operational collaboration. The private sector and the U.S. government have engaged in and experimented with technical and legal models, globally, to disrupt and dismantle cybercrime infrastructure. Efforts to date illustrate that a collaborative multi-stakeholder approach – sharing actionable information and leveraging the combined capabilities of the private sector and the government – yields the best opportunity to disrupt cybercrime quickly and at scale.

The recent take down of Emotet, a botnet known to support the distribution of the Ryuk ransomware, involved law enforcement around the world as well as private sector security researchers. Individual computers infected with malicious software are called bots. These bots are controlled by the cybercriminal to create a botnet –that can be used to engage in further criminal activity. These botnets can range from a few hundred to tens of millions of compromised systems. In taking down the Emotet botnet, law enforcement seized assets and arrested the cyber criminals in Ukraine while researchers working with law enforcement took down Emotet’s command and control infrastructure used to operate the botnet and cleaned the individual computers in the botnet. The effort involved a worldwide coalition of law enforcement agencies across the U.S., Canada, the UK, the Netherlands, Germany, France, Lithuania, and Ukraine to disrupt and take over Emotet’s infrastructure which was located in more than 90 countries[4] – while simultaneously arresting at least two of the cybercriminals.

As the U.S. government has recognized, for example, with the creation of the new interagency ransomware taskforce and the FBI’s new cyber strategy, unilateral action, whether public or private, is not a sustainable solution against nation-state sponsored or financially motivated sophisticated organized cybercrime. To combat ransomware we recommend:

- Clearly understanding the problem: Cybercriminals currently take advantage of the internet and the limitations of sovereignty to carry out crime against victims located anywhere in the world. While the internet and technological tools enable cybercriminals to operate with almost absolute anonymity.

- Focusing on what can be done to address the problem: Disruption of malicious infrastructure, even when arrest is not possible, through global cooperation between the private sector and governments.

- Increasing focus on critical areas: To increase the scope and scale of disruptions, and to have success similar to Emotet, public-private information sharing, strong global Mutual Legal Assistance, technical operational capabilities and training, threat tracking and prioritization, and victim remediation needs to be improved.

A collaborative, multi-stakeholder approach to countering cybercrime, including ransomware must be nimble and function at scale. Though the bulk of government efforts have been driven by traditional law enforcement objectives and tactics (e.g., indictment and arrest), we now see a shift in the U.S. government and foreign governments to actions to disrupt cybercriminal infrastructure. Traditional enforcement mechanisms are a critical piece of global cybersecurity and U.S. national security; however, we must continue to focus on the more immediate “takedown” or disruption of infrastructure, which more strategically aligns with the needs and priorities of many victims and is a significant public interest. This focus on disruption should be a primary strategy to combat ransomware.

VI. Conclusion

I am pleased to see that the U.S. Government, the security community, state and local governments, and the international community are coming together for a coordinated response to ransomware. There is much work that needs to be done but I am optimistic that we collectively have the thought leadership to accomplish our goals. The IST Ransomware Task Force published a set of thoughtful and measured policy and operational recommendations, including several that may require legislative action. I encourage all stakeholders involved to act where they can to reduce the incidence of ransomware attacks.

[1] The Task Force recently published a framework of actionable solutions aimed to mitigate ransomware as a malicious cyber activity and criminal enterprise: Institute for Security and Technology (IST) » RTF Report: Combatting Ransomware

[2] See also Parents were at the end of their chain – then ransomware hit (nbcnews.com)

[3] Hiltzik: The threat of ransomware – Los Angeles Times (latimes.com)

[4] Cops Disrupt Emotet, the Internet’s ‘Most Dangerous Malware’ | WIRED