Amid the current need to continually focus on the COVID-19 crisis, it is understandably hard to address other important issues. But, this morning, Washington Governor Jay Inslee has signed landmark facial recognition legislation that the state legislature passed on March 12, less than three weeks, but seemingly an era, ago. Nonetheless, it’s worth taking a moment to reflect on the importance of this step. This legislation represents a significant breakthrough – the first time a state or nation has passed a new law devoted exclusively to putting guardrails in place for the use of facial recognition technology.

In 2018, we urged the tech sector and the public to avoid a commercial race to the bottom on facial recognition technology. In our view, this required a legal floor of responsibility, governed by the rule of law. Since that time, the issue has migrated around the world with a wide range of reactions, with some governments banning or putting a moratorium on the use of facial recognition. But, until today, no government has enacted specific legal controls that permit facial recognition to be used while regulating the risks inherent in the technology.

Washington state’s new law breaks through what, at times, has been a polarizing debate. When the new law comes into effect next year, Washingtonians will benefit from safeguards that ensure upfront testing, transparency and accountability for facial recognition, as well as specific measures to uphold fundamental civil liberties. At the same time, state and local government agencies may use facial recognition services to locate or identify missing persons, including subjects of Amber and Silver Alerts, and to help keep the public safe. This balanced approach ensures that facial recognition can be used as a tool to protect the public, but only in ways that respect fundamental rights and serve the public interest.

While regulation in this field will clearly evolve, Washington’s new law provides an early and important model. Some of the new law’s features are especially important.

Testing requirements

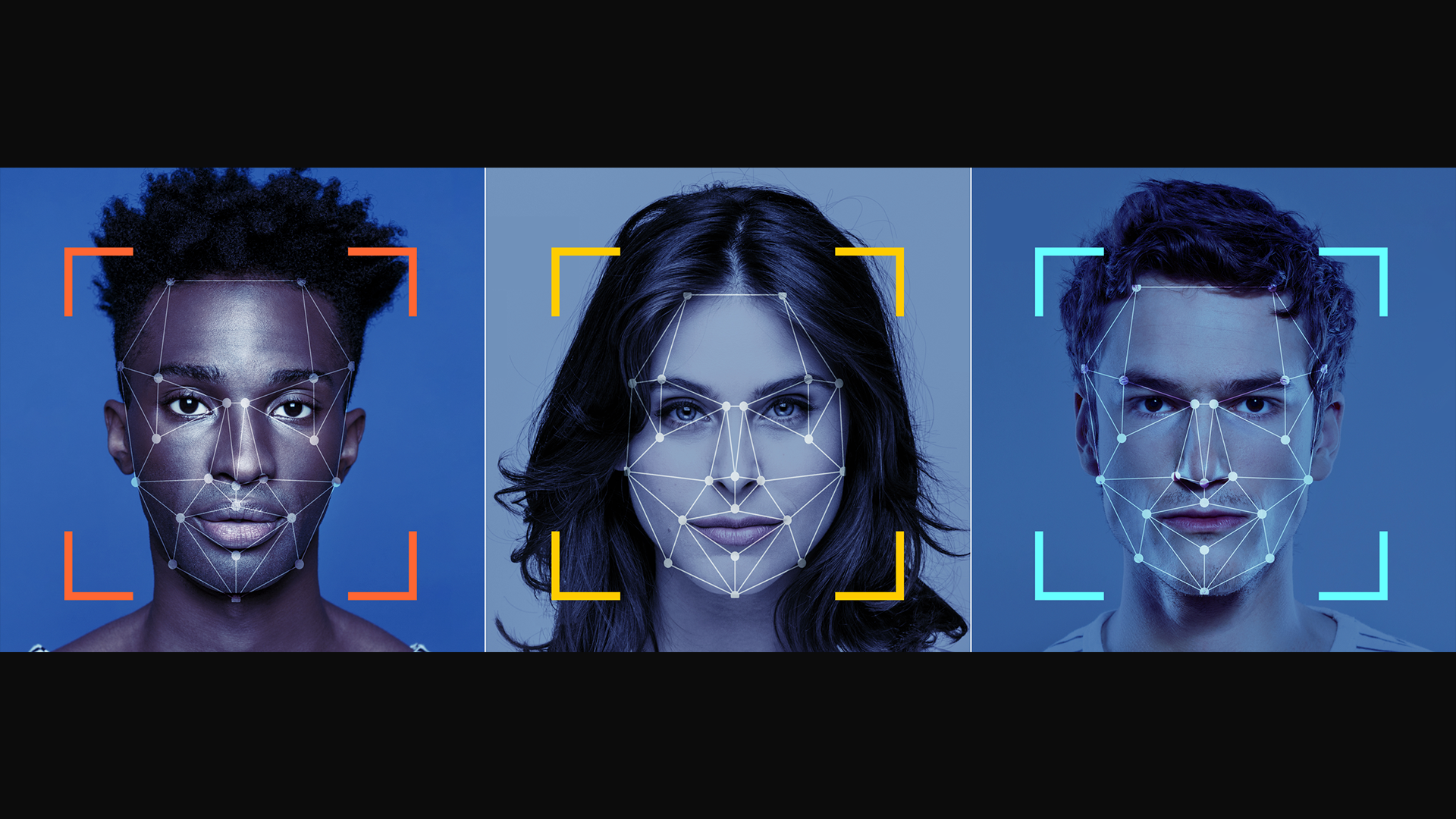

First, the law will accelerate market forces to address the risk of bias in facial recognition technology. Beginning next year in Washington, a state or local government agency can deploy facial recognition only if the technology provider makes available an application programming interface (API) or other technical capability to enable “legitimate, independent and reasonable tests” for “accuracy and unfair performance differences across distinct subpopulations.” In addition, vendors must disclose “any complaints or reports of bias regarding the service.”

In our view, this approach is both necessary and pragmatic. The risk of bias is real. Recent NIST research demonstrated that some facial recognition technologies have encountered higher error rates across different demographic groups. As documented in the “Gender Shades” research, this problem arises when trying to determine the gender of women and people of color. As we’ve found, no customer wants to purchase a facial recognition service that is flawed. But, without the ability to subject these services to third-party testing, it is impossible to know the accuracy of the available technologies. Thus, market forces cannot work effectively to push tech companies to improve their technology as quickly as they should. Washington’s new law shows how regulation and market forces can move forward together in a way that advances innovation to meet public needs.

Transparency and accountability

The new law also advances two other ethical and human rights principles that are fundamental for all aspects of artificial intelligence (AI): transparency and accountability. Before a state or local agency can begin to use facial recognition, it must first file a public notice of intent and “specify a purpose for which the technology is to be used.” This ensures that the public is informed at the very beginning of the technology adoption process.

Perhaps even more important, the new law also establishes a thorough accountability model for public adoption of facial recognition technology. Agencies that use facial recognition must establish “a clear use and data management policy” (including detailed protocols that control how the technology will be deployed), data integrity and retention policies, and strong cybersecurity measures. They must also provide the public with information about the facial recognition service’s “potential impacts to privacy” and the service’s “rate of false matches, potential impacts on protected subpopulations, and how the agency will address error rates, determined independently, greater than 1%.” This is all subject to public consultation requirements, including notice and comment processes, and community consultation meetings.

The law also requires that humans, not machines, be responsible for decisions using facial recognition technology, which is an important check on how these systems can be used. For example, if the use of facial recognition would result in a potential denial of service, a human must verify the individual’s identity to avoid decisions based on false results. This obligation to ensure “meaningful human review” naturally requires well-trained personnel. The new law therefore requires that agencies must conduct periodic training for everyone who operates a facial recognition service or who processes personal data obtained from it. This training must cover both the capabilities and limitations of the service, as well as how to interpret facial recognition output.

Protection of civil liberties

Through some of the new law’s most important provisions, Washington state has become the first jurisdiction to enact specific facial recognition rules to protect civil liberties and fundamental human rights. While the public will rightly assess ways to improve upon this approach over time, it’s worth recognizing at the outset the thorough approach the Washington state legislature has adopted.

First, there is protection against mass surveillance. Under the new law, a public authority may not use facial recognition to engage in “ongoing surveillance, conduct real-time or near real-time identification, or start persistent tracking” of an individual except in three specific circumstances. These require either (1) a warrant; (2) a court order “for the sole purpose of locating or identifying a missing person or identifying a deceased person;” or (3) “exigent circumstances,” a well-developed and high threshold under state law.

Second, there is added protection for specific human rights. For example, the authorities may not use facial recognition to record any individual’s exercise of First Amendment rights. In addition, an agency may not use facial recognition based on a person’s “religious, political or social views or activities” or “participation in a particular noncriminal organization or lawful event.” Similarly, they may not use the technology based on a person’s “actual or perceived race, ethnicity, citizenship, place of origin, immigration status, age, disability, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation or other characteristic protected by law.”

Third, there are procedural safeguards for criminal trials. For example, authorities must disclose their use of facial recognition technology to criminal defendants in a timely manner prior to trial. This will provide defendants with the right to challenge the use of the technology if it’s flawed or was used unlawfully.

Fourth, there are detailed transparency requirements relating to civil liberties. The new law details public reports on the warrants that were sought and granted for the use of facial recognition. These reports include information on the number and duration of any extensions of the warrant, the agencies that sought the warrants and the nature of the public spaces where surveillance was conducted.

Putting Washington’s new law in context

Finally, it’s important to consider Washington’s new law in the context of the broader developments in AI that are both advancing the public’s needs and putting the world’s timeless values at risk.

First, a new law in no way absolves tech companies of their broader obligations to exercise self-restraint and responsibility in their use of AI. As of today, only one U.S. state out of 50 provides the public with the specific protection they deserve when it comes to facial recognition. The first question for the rest of the world is whether tech companies will step forward voluntarily to adopt and implement responsible AI principles. We should all hope that more tech companies will do so – and that customers will reward those who act responsibly.

Second, the new law is a testament to what legislative leaders can accomplish when they focus not just on whether facial recognition should be used, but how. Many facial recognition debates, including one that took place last year in Washington state itself, have foundered in gridlock over whether to ban this new technology. But, as this new law so clearly illustrates, there is so much to be gained from more thorough consideration of ways to protect the public from the risks of facial recognition by regulating its beneficial use. We owe a special thanks to the legislative leaders who led the legislature’s consideration of these issues, including Representative Debra Entenman and Senator Joe Nguyen, who also works as a Microsoft employee when not spending time in our state capital when the legislature is in session.

Ultimately, as we consider the continuing evolution of facial recognition regulation, we should borrow from the famous phrase and recognize that Washington’s law reflects “not the beginning of the end, but the end of the beginning.” Finally, a real-world example for the specific regulation of facial recognition now exists. Some will argue it does too little. Others will contend it goes too far. When it comes to new rules for changing technology, this is the definition of progress.