Imagine how frustrating it is to live in a community that has limited access to the internet – that means limited access to the education, economic and healthcare opportunities that enable individuals and communities to prosper and grow. Complicating the problem further, the data gathered and reported by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) about the availability of broadband access in rural communities is flawed. Unfortunately, that flawed information is often used by federal, state and local agencies to determine where to target funding to close the broadband gap.

Our experience tells us that this is not a hypothetical situation. It is real, and it is likely widespread across much of rural America.

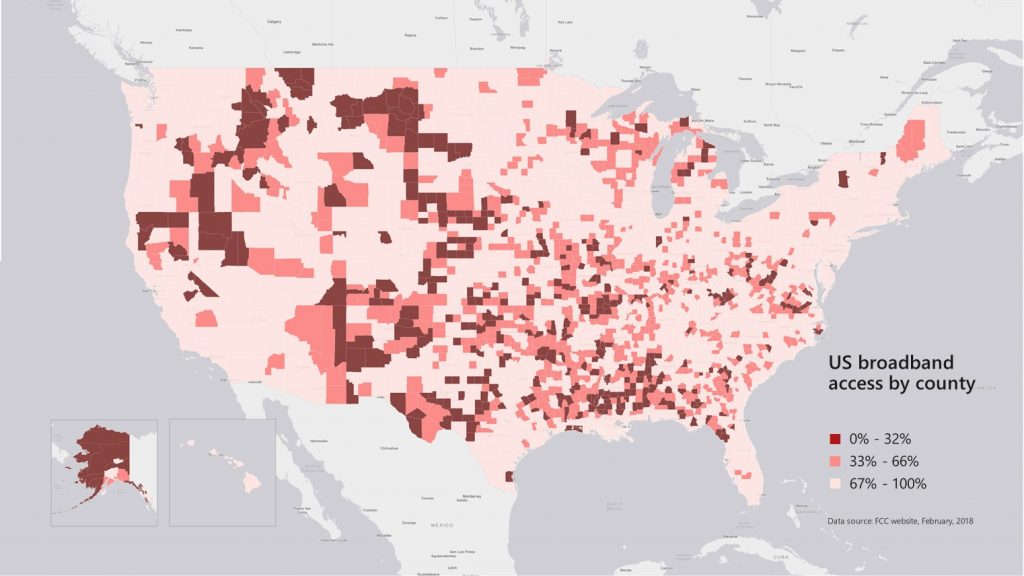

Under federal law, the FCC is tasked with collecting data and issuing reports on broadband availability in the U.S. The FCC requires about 3,200 broadband providers across the country to twice yearly submit broadband availability data. Based on the most recent data collected, the FCC reports that there are about 24 million Americans lacking broadband access – defined as a connection providing minimum download speeds of 25 megabits per second (Mbps) and minimum upload speeds of 3 Mbps. Most of those people – over 19 million – lacking access to broadband are located in rural areas, meaning that about 31 percent of people living in rural areas in the U.S. lack broadband access.

However, we have reason to think there are a number of places in rural America being miscounted as having broadband available to them. This is because broadband providers are only required to report areas where it could hypothetically deliver broadband access, not just the areas where they actually do provide broadband access. The aggregate number then reported on by the FCC implies a higher number of people in those rural communities have broadband available to them when in reality they do not.

Consider a rural county in which the FCC’s data reports that broadband is available everywhere – that maybe two out of six fixed broadband providers claim to provide service to the entire county. In fact, these two providers, while they could provide broadband access, don’t actually offer any broadband service to the residential customers in that county. And if they did, it would cost those customers over $250 per month for broadband.

This situation is all too common in counties all across rural America and is frustrating for the people who live there. Broadband connectivity is an increasingly critical part of accessing better educational opportunities, jobs and healthcare. Broadband is the electricity of the 21st century and without it citizens are unable to participate in our growing digital economy.

For example, a real estate agent in a rural county explains that availability of broadband guides whether people move to his county and is causing many people to leave for better-connected areas: “As a Realtor, I can tell you one of the first things people ask about is if high-speed internet is available.” Another local citizen on a community chat board sums up the situation, “Our internet is pathetic! Literally one step above dial-up. It is through [name removed], but there wouldn’t be any way that you could run a business off of this service. Slow…. Trying to watch a video is painful!”

Through our Airband Initiative, Microsoft is working with rural broadband providers across the U.S. to help close the digital divide and provide broadband access to 2 million rural Americans by July 4, 2022. Through this work we have learned that confidence in the FCC’s pronouncements of broadband progress in rural areas remains a work in progress and uncertainty over how broadband deployment is defined is leading to less rural investments where it is needed.

Fortunately, the FCC is looking at ways to improve its broadband data collection.

A good place to start would be to distinguish between the data for places that broadband providers actually serve and those that they could hypothetically serve. Microsoft recently submitted a proposal asking the FCC to include in its data collection only those census blocks where broadband has actually been deployed and eliminate, or at a minimum segregate information on where people hypothetically could be served.

In addition, we are proposing that the FCC further reduce burdens on broadband providers by moving from twice yearly to annual reporting. To improve data accuracy, further ease reporting obligations and enhance data analysis, the FCC also should implement online visualization and analytics tools. We also support efforts by the U.S. Department of Commerce’s National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) to work with nonprofits, academia, the private sector and others to voluntarily obtain additional broadband data, and we support efforts by state governments to better assess broadband availability.

The simple actions described above would go a long way to identifying those lacking access to broadband and better targeting needed investment and support to those communities.