Matt Stempeck is Director of Civic Technology on Microsoft’s Technology & Civic Engagement team. The thoughts in this post are derived from a collaboration with Micah Sifry and Erin Simpson, which will be presented today at The Impacts of Civic Technology Conference. Micah Sifry co-founded the long-running Personal Democracy Forum conference and Civic Hall, which has attracted over 1,000 individual and 90 organizational members in just over one year of operation. Erin Simpson is Program Director of Civic Hall Labs, and previously a Microsoft Technology & Civic Engagement Fellow.

The field of civic technology is poised to take off. Investors, philanthropists, and the media see a gathering force, a convergence of trends. The technology industry’s increasingly interested in societal impact. Governments are developing the capacity to leverage advanced technologies. Communities are being expected to accomplish more with fewer resources.

We believe the field is at an inflection point. We have organized a taxonomy of civic tech to attract more participation to the field, move resources in productive directions, and crucially, understand impact.

Our taxonomy consists of four parts:

- A clear definition of civic tech.

- A categorical index of civic tech’s technical functions.

- A study of the social processes in which we engage.

- Cross-cutting analytical questions that get to the heart of what it all means.

- What is civic tech?

This is the quick hit sentence you can share with someone at a party that still leaves room for them in the conversation:

This definition is intentionally broad. We see civic tech as an umbrella term that captures subcategories like government tech, but expands beyond the government, as well. Depending on where you live, not every government works for the public good. Civil society includes, but is not limited to, the state.

Civic tech spans everything from public policy to political campaigns to nonprofits to urban planning to statecraft. In addition to closely adjacent fields, civic tech benefits from closely related work that set the stage and provided the context for what we do today: the open source movement, government transparency advocacy, and even work to improve access to the open Internet played critical roles in the development of what we now call civic tech.

These previously distinct fields have met at the intersection of tech, each field forced to reconsider profound shifts in participation and empowerment and the new challenges they present. This convergence becomes immediately clear when you browse Civic Graph, a network visualization the Microsoft Technology & Civic Engagement team built to make legible the many interconnections.

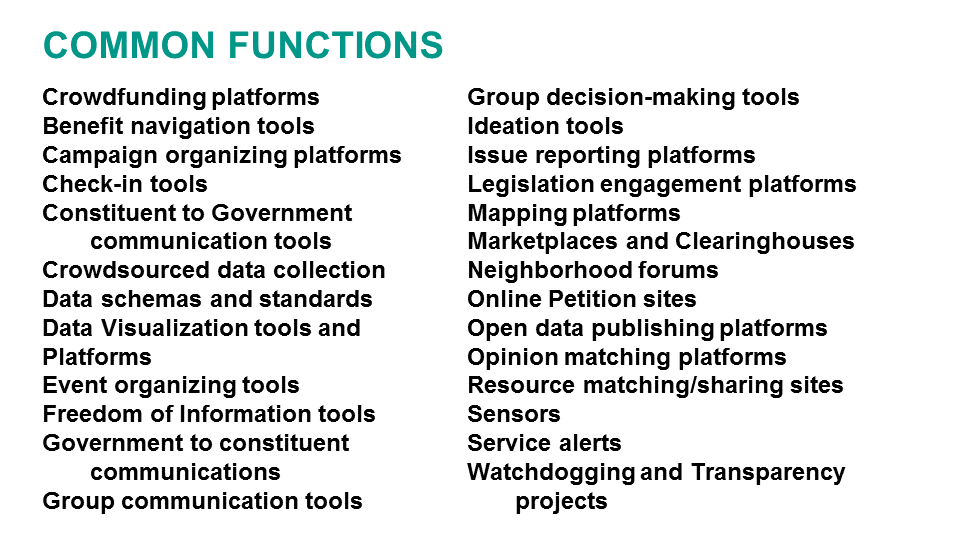

II. Technical functions

A broad convergence of fields naturally invites a rich variety of actors attempting different objectives. We’re better for it. For practitioners and researchers in the field, we need names for the subgroupings within which we actually work. So we’ve inventoried hundreds of actual examples of civic tech and organized them into categories by the functions they achieve. We took a bottom-up approach, beginning with what exists rather than our own opinions. The result is a list of functional categories:

The categories and their examples can be found here. We applied the categories only after the examples were on the table, with the full knowledge that it’s still an incomplete list. Entire categories of technologies are yet to come, while other categories may go. Some technologies ignite founders’ visions and funders’ passions without finding a good product-market fit.

One thing you may notice is that we avoid domain-specific examples wherever possible. Solutions for improving health, education, cities, elections, should all be included in civic tech when solving for shared challenges and opportunities, but to categorize the tech, we refined down to the core technical function. It’s also important to note that our collection includes failed efforts, as we consider these data points as vital to understanding the field as the success stories (and perhaps more so, given the disparity in awareness between successes and failures).

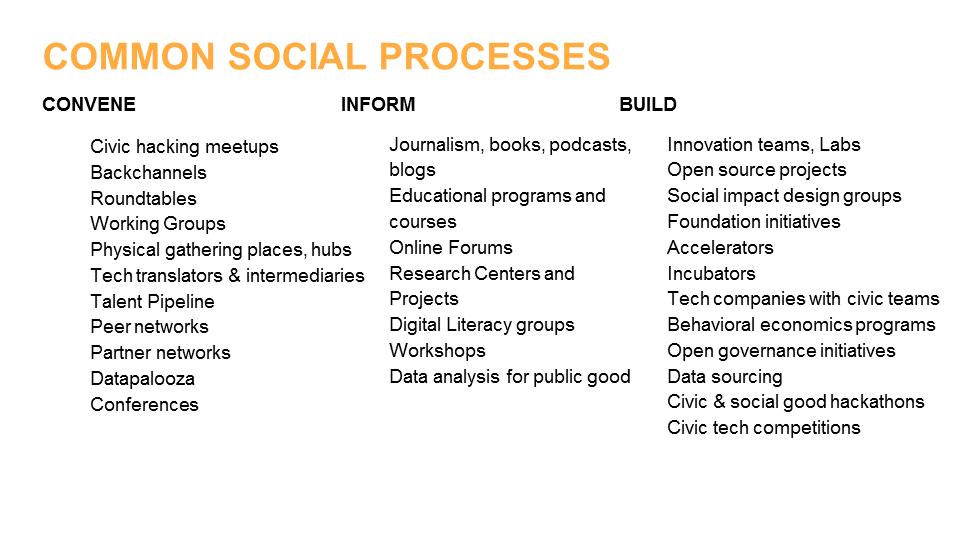

III. Social processes

If we were to stop here, we would have a categorical compendium, but not a taxonomy. We need to consider the social processes in which we work together to employ the technologies, and a way to evaluate to what that amounts.

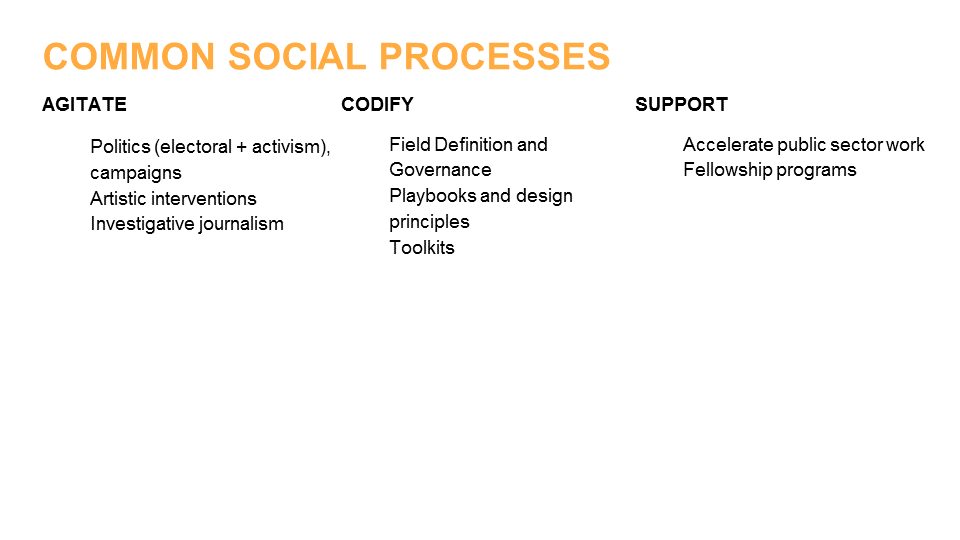

Civic tech is so much more than tools and platforms and the groups who make them. The civic tech ecosystem necessarily includes the social processes we use to organize the talent and relationships that are key to driving impact. We inventoried these expressed behaviors, from relatively new formats of hackathons and globally distributed open source projects to time-honored traditions like gathering in shared spaces built around shared values.

This list is also not exhaustive, but begins to demonstrate just how much of the work of civic tech is interpersonal.

This list is also not exhaustive, but begins to demonstrate just how much of the work of civic tech is interpersonal.

IV. To what end?

Civic tech’s practitioners have achieved significant victories and seen some of their ambitions plateau. To facilitate research into the impacts of this work, we must confront cross-cutting analytical questions that get to the true meaning of the tech – what does it do out in the world?

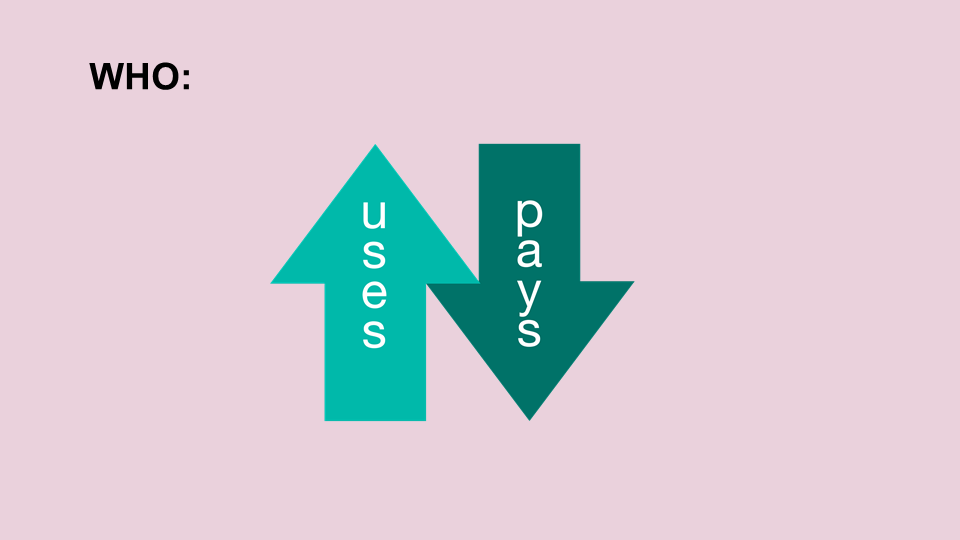

One way to evaluate civic tech projects was suggested to us by Tom Steinberg, who founded MySociety, a proto-civic-tech organization, and committed resources to asking hard questions about its impact. Tom suggested we evaluate civic tech along the axes of who uses it (users) and who pays for it (customers). Users can be customers, although it’s often the case in civic tech that the people and groups funding the work are not the intended beneficiaries. Governments, organizations, and individuals most often use civic tech, whereas governments, philanthropies and industry most often fund civic tech. Evaluating civic tech through the lens of users, customers and other stakeholder groups involved helps us unpack tensions as well as successes. Microsoft’s Elizabeth Grossman suggests the additional axis of “Who executes?” which includes “who builds?” and “who maintains?” When we consider complicated tasks like algorithm design for public benefits allocation, or behavioral science for policy outcomes, knowing the designers of the black box matters. Taken as a set, these questions can quickly cut to the purpose, stated or otherwise, of many civic tech works.

Another cross-cutting question to consider is the degree of change a civic tech effort seeks to affect. We apply a framework introduced by Tony Roberts that categorized projects by the depth of change they seek: conformist, reformist, and transformist. A civic tech project could conform to existing power dynamics, and simply digitize the existing world. A civic tech project can also reform, providing efficiencies and conveniences and generally improving the status quo. Or, a civic tech project can transform what’s possible, and actually shift power relationships from the few to the many.

Lastly, we consider the depth of the technology. A civic feature embeds civic engagement into mainstream tech, like when a search engine informs its users about presidential election candidates. I collect prominent examples of civic features.

Civic products are stand-alone tech products built around one or several specific civic use cases. These are the most obvious examples of civic tech, and the most common examples in our collection.

Civic externalities are produced by technologies that weren’t necessarily intended to affect civic life, yet most certainly do. Take, for example, how Twitter has made conversations more transparent and accessible to broader publics. The reduced friction between conversations in this open communications medium has produced positive and negative externalities ranging from increased awareness of social justice issues African-American communities face to targeted group harassment of individual females.

Today, in Barcelona, we’ll share this work with peers from around the globe and invite their critiques and contributions. There will be Post-It notes. We’d love your thoughts, reactions, and contributions (which you can add here). We’ll continue refining and building this model to grow the field of civic tech and deepen our understanding of its impact.