Buttoning your shirt, writing a quick note to a co-worker, using a fork and knife (or a set of chopsticks). Every day we perform tasks like these with the greatest of ease—automatically, even, to the point that they’re labeled as ordinary and menial.

But the biomechanics behind each task are anything but ordinary, involving the interplay between two hands, each containing 27 bones, more than 30 muscles, nearly 50 nerves and 30 or so arteries.

Fueled by their fascination with the human hand, and firm beliefs in the need for continued explorations of more natural input methods, Bill Buxton and Ken Hinckley assembled a team of researchers from Microsoft Research (MSR), Cornell University and the University of Manitoba. Their goal: tap into the hand’s dexterity and explore new frontiers in human-computer interaction.

The implements they focused on were the tablet and stylus, and the result of their labor is some groundbreaking research that has won a Best Paper Award at UIST 2014 (User Interface Software and Technology Symposium), which is occurring this week in Hawaii.

“There’s a reason Picasso used a paintbrush instead of finger painting all the time, just as there’s a reason a dentist uses precise drills, which are basically just specialized styluses, as opposed to a chisel,” says Buxton. “The fingers and hands have this absolute dexterity, both alone, such as when you pinch and zoom on a touch screen, but also through tools that you hold in your hand. So when we think about a stylus, it’s just another long, skinny tool that we can do amazing things with.”

As it turns out, very little has been done to dissect the fine motor skills of the hand—the way in which a person tucks a pen between their fingers when writing, erasing or resting, or the manner in which your dominant and non-dominant hands work together. It’s these “seen but unnoticed” details that Ken and Bill believe hold the key to creating a stylus worthy of the capabilities and potential of the hands in which it is held.

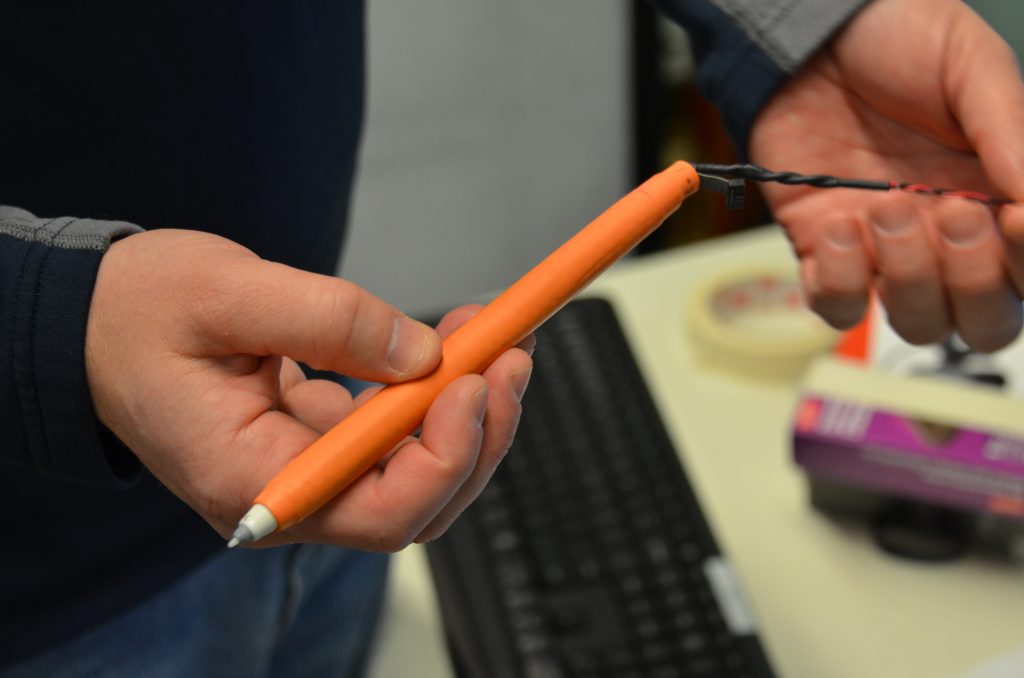

As part of their research, the team worked closely with the prototyping lab here at Microsoft to create a tablet and stylus, each of which contains inertial sensors to study these details. Working together, they can track for nine degrees of freedom—the position of each device, as well as their relative orientation.

In addition, the barrel of the stylus is encased in a multi-touch grip sensor that monitors the person’s grip and lets them start or end a task with the simple tap of their finger. The tablet features full grip sensing, which provides additional clues about the user’s intent.

With the hardware in place, Ken says it was just a matter of “stretching their minds” and coming up with one idea after another to explore.

Says Ken: “Our goal was to factor out the interface and provide as simple an experience as possible. So throughout the process we kept asking ourselves, ‘how do we use this understanding of device grip and orientation to add new possibilities, but without drowning the user in more complexity?’”

As you’ll see in the video, they’ve forged a new frontier of possibilities with a stylus, creating a tool that truly extends the interplay between both hands into the digital working environment. It will be exciting to see what new scenarios this research enables in the future.

Learn more about MSR’s presence at UIST by reading this Microsoft Research story.