Shiva Kumar teaches in the sweltering farmlands of southern India, but when he wants his students to learn about other cultures, he whisks them to exotic locations at the ends of the earth. Kumar’s students have traveled millions of miles around the world, virtually, through the Skype sessions he began arranging in 2015.

“We found out that six kids were sharing one textbook in another location, and my students were shocked to learn of the difficulties they have and yet see the empathy flowing among them despite it all,” Kumar recalls. “My students realized there are a lot of poor people in the world, and it inspired them to start sharing more amongst themselves. Even small things like lunch, or a pencil or eraser, or sports equipment — they began sharing everything.”

For this year’s Skype-a-Thon, an annual event to be held Nov. 13 and 14, the students in Kumar’s 10 science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) classes will bring their sleeping bags to school so they can do eight-hour shifts of 30-minute Skype sessions. The two-day marathon of virtual travel has become a staple for Kumar’s classes ever since the first one four years ago, when the students’ connections with classrooms around the world spanned more than a million miles. The kids decorate their school with lights and showcase their Indian culture through traditional dances and musical instruments, as well as modern STEM projects.

Last year, almost half a million students from more than 90 countries participated, traveling 14.5 million miles. The goal is to meet or exceed those figures this year.

And this year, the students’ efforts will provide a tangible benefit. For every 400 miles virtually traveled in the Skype-a-Thon, Microsoft will donate the resources for a student to attend school in one of the nine WE Villages in Asia, Africa and Latin America, with a goal of helping 35,000 kids. The WE Villages international development model is part of WE, an organization that also includes WE Schools, which focuses on empowering kids to create change locally and globally.

“Children helping children through education – that’s how our mission to ‘make doing good doable’ started out,” says Erin Barton, chief development officer for WE. “We’ve got youth who are privileged enough to have access to technology, and now they’re giving the opportunity to others to have access to gain an education themselves.”

“Skype provides a gateway for students to learn about other people, within the curriculum teachers are teaching,” says Anthony Salcito, vice president of worldwide education for Microsoft. “And it’s not a one-way street – kids in developing countries use their talents to help kids elsewhere. It’s just the beginning of opening up peace across the planet and enabling kids to see their world differently.”

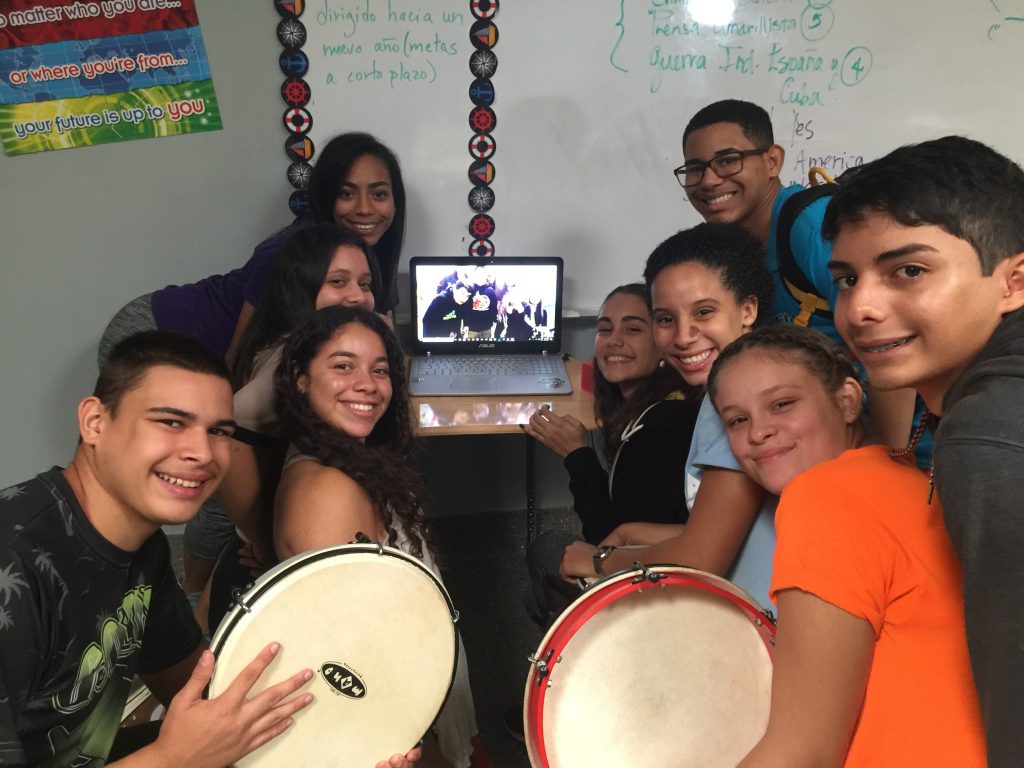

Darlene Colon, who teaches technology and English as a second language to middle schoolers at a public school for athletes in Puerto Rico, has started a monthly rotation of Spanish and English sessions with classes in Texas and Kentucky. The kids are helping each other with pronunciation, she said — a welcome diversion for her students, who are still struggling from the impact of Hurricane Maria last year.

Colon’s school building was destroyed in the hurricane, about two months before last year’s Skype-a-Thon. A hallway in a neighboring school became her classroom, and even though the area still didn’t have electricity, she found a way to charge her computer and boosted the data service on her phone so she could connect her class for the event.

“The kids didn’t have anything, no electricity or water. Some had lost their homes, family members and friends, and they were very stressed,” she says. “So this helped them forget their troubles and just enjoy themselves.”

When the electricity came back on in time for Christmas, her students’ joy was so infectious that a spontaneous music jam and dance broke out during a Skype session with a class in New York.

“Everyone was so happy, and even though all the news was about the chaos here, we were able to show that wasn’t necessarily the whole story,” she says. “Even though it was difficult for us, we were willing to continue and participate.”