It starts with a better mosquito trap.

Then come the more autonomous drones, the cutting-edge molecular biology and the advanced cloud-based data analysis.

And, finally, the big payoff: Project Premonition, a system that aims to detect infectious disease outbreaks before they become widespread, with the goal of preventing major health disasters.

It may sound like the stuff of blockbuster movies, but Project Premonition aims to be fact, not fiction. Microsoft researchers are working with academic partners across multiple disciplines to develop the system, which collects and analyzes mosquitoes to look for early signs that potentially harmful diseases are spreading.

“We’re really pushing the envelope in many ways,” said Ethan Jackson, the Microsoft researcher who is spearheading the project.

The initial work on Project Premonition, including a feasibility study the researchers did in Grenada in March, will be presented publicly Wednesday at TechFair, a Microsoft innovation showcase in Washington, D.C.

The researchers expect that it will take several years to complete all the elements of the research. But, they say, Project Premonition could eventually allow health officials to get a jump start on preventing outbreaks of a disease like dengue fever or avian flu before it occurs, whether or not it is a disease spread by mosquitoes. It will do that by relying on what Jackson calls “nature’s drones” – mosquitoes – to look for early signs that a particular illness could be on the move.

“The ability to predict an epidemic would be huge,” said Douglas Norris, a professor of molecular microbiology and immunology at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health who is working on the project.

That’s a huge leap forward from the current system. Usually, health officials only find out about an outbreak once people are already getting sick. This means things like vaccines and health clinics may not be up and running for as long as a couple of months after a disease has begun spreading, said James Pipas, a professor of molecular biology at the University of Pittsburgh who also is working on Project Premonition.

“If you know they’re coming, you can prepare your response ahead of time,” he said.

Better traps and safer, smarter drones

Even as they work toward that long-term goal of anticipating outbreaks, the researchers say they expect the project to have more immediate benefits in several key fields.

“This is at least a five-year vision, no doubt about it,” Jackson said. “But along the way, the advances we make in each of these areas have a lot of value in their own right.”

That starts with the mosquito trap.

Norris, the Johns Hopkins professor, has spent most of his adult life studying mosquitoes and ticks, and the diseases they transmit. That means he often finds himself in far-flung places such as Brazil and sub-Saharan Africa, collecting mosquitoes using traps that are little changed from the designs of the 1950s and 1960s.

The traps are fraught with challenges.

They require batteries that are expensive and have to be changed several times a year. Some experiments even require chemicals to be transported by ship because airplane safety regulations won’t allow them to travel by air.

Ideally they use dry ice as bait, but that’s impossible to get in parts of Africa so Norris and other researchers have to make do with other improvised solutions, such as placing the traps next to chickens or even people who are sleeping under mosquito netting.

The traps also collect other bugs indiscriminately, so entomologists must spend hours sorting through what Norris calls the “soup” to get the mosquitoes out.

“You have a few mosquitoes in this big pile of stuff,” he said. “It’s like looking for this one Lego guy’s head in the pile of Legos.”

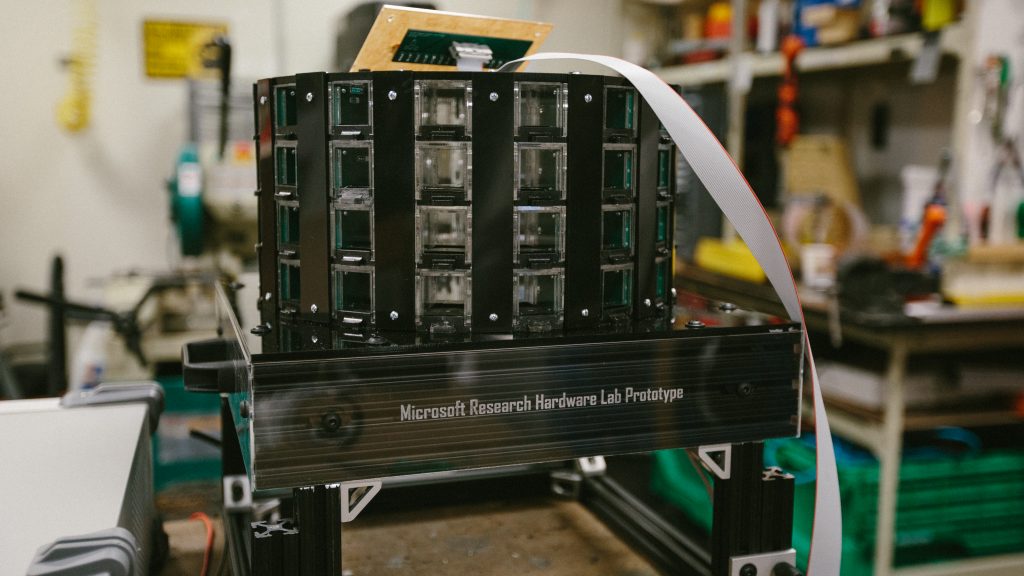

The Project Premonition mosquito trap design uses less energy and relies on lighter weight batteries. It also has a new bait system for luring mosquitoes, a sensor that automatically sorts the mosquitoes from the other bugs and chemicals that can preserve the mosquitoes for lab study. It is expected to be significantly cheaper and lighter than current traps.

Norris said those improvements could save countless hours of lab work.

“Any one of them would be a huge advantage to people who work in the field,” Norris said. “It’s like a Holy Grail. It would be awesome.”

Safer cyber-physical systems

Then there’s the drones. For Project Premonition to work, Jackson’s team will rely on drones that can fly the mosquito traps into and out of remote areas in a semi-autonomous way, rather than having to be constantly directed from the ground.

Microsoft researchers are beginning to develop ways to make the drones more autonomous, and they also are working with Federal Aviation Administration officials on regulatory requirements.

Jeannette Wing, Microsoft’s corporate vice president overseeing the company’s core research labs, said the ability to make drones that can carefully navigate an environment on their own is key to another, broader goal of Project Premonition: Building safer cyber-physical systems.

A cyber-physical system is any computer-based system that interacts with the real world, including everything from implanted medical devices to drones to driverless cars. It’s much more complicated to safeguard a cyber-physical system than, say, a software program because there are other factors to think about beyond just code, like wind, temperature or pedestrians.

As people grow more dependent on these types of systems, and the Internet of Things evolves, Wing said computer scientists need to be thinking ahead about ways to ensure that they are safe before they are in wide use.

“The safety of all these cyber-physical systems is paramount,” she said. “We need to get ahead of the game.”

Advanced analytics

Once the mosquitoes have been collected, the next challenge is to analyze them for microbes and viruses that could pose a threat to humans.

Until recently, the idea of culling through mosquitoes to try to find diseases that are both known and unknown would have been wildly impractical.

“Even five years ago, the cost of a system like this would have been too high,” said Jackson, the Microsoft researcher.

Instead, researchers would painstakingly look through samples to try to find one specific disease, such as malaria.

But now, the latest developments in molecular biology and genetic sequencing are allowing researchers to cull through samples to look for multiple viruses, including ones that haven’t been discovered yet, said Pipas, the molecular biologist.

Researchers can then create cloud-based databases of the information they find, and come up with algorithms for evaluating which of these viruses could present a threat to humans or animals that humans rely on.

Pipas also is doing similar research with sewage, and he said he’s finding that the majority of viruses they see haven’t even been discovered yet.

He expects that it will be very difficult to figure out which of the viruses they identify in mosquitoes are a threat, but he also says such a system holds incredible promise for preventing outbreaks.

“That’s the kind of thing that gets me really, really excited,” Pipas said.

Allison Linn is a senior writer at Microsoft Research. Follow her on Twitter.