Jared Spataro loves his wife—and his kids. So he was blindsided when, nearly 20 years ago, she came to him with a question: “So...when are you going to file for divorce?”

He’d been rising through the ranks at a burgeoning software company, working on a fast-growing collaborative content management business. It was the biggest thing he’d ever done, and he was struggling to keep up with the relentless pace. He started waking up earlier and earlier, thinking if he could just start work at 3 a.m.—okay, 2 a.m.!—he could get it all done.

His wife and four young kids were paying the price. “You spend no time with me,” his wife told him. “If I’m important to you, I sure can’t tell.” That’s when it hit him. “There were always going to be more demands from the business, and I had to draw the lines,” Spataro says.

After talking with a mentor at his company and reading William Oncken’s Managing Management Time , he started a practice that organizes his life to this day. “Timeboxing” is the principle of choosing the most important areas of your life—from family to exercise to community to, yes, work—and laying them out on your calendar with precise start and stop times. “There are 10,080 minutes in a week,” says Spataro, who is now corporate vice president of Modern Work at Microsoft. “You can be the boss of all those minutes if you take control.”

In a world of flexible work, where people have the agency to work from different places at different times, the lines between work and life are blurrier than ever. Work creeps into the time we used to spend unwinding with a glass of Malbec or reading bedtime stories to our kids. And when you’re working from home, it’s easy to flip open your laptop as soon as you wake up because you don’t need to shower, put on real pants, or catch a bus to the office. It’s up to each of us, Spataro contends, to define those lines for ourselves. “When you have constraints, you actually solve problems,” he says. “Timeboxing enforces those constraints for you.” It’s a proven method: according to one analysis of productivity tips, timeboxing is the most useful.

“When you have constraints, you actually solve problems. Timeboxing enforces those constraints for you.”

Central to the practice is the understanding that you can’t have it all—we all have to decide where to spend our minutes. The first step, then, is choosing your priorities, which become the basis for your boxes. (Spataro recommends no more than five, as more than that becomes difficult to juggle.) His boxes? God, family, health, sleep, and work.

Take a random Monday. Spataro wakes up at 4 a.m. and spends three hours doing daily worship and working out. At 7 a.m., the work box starts. That box contains smaller boxes, Russian nesting doll–style, designating what he needs to get done for the day—his to-do list grafted onto his calendar. For example, from 1:30 to 2:15 p.m., there might be a box blocked off to prepare for a customer meeting.

“It forces me to look at each day and say, ‘What do I have to get done? How am I using my time?’” If he needs to work on next year’s budgets but has no minutes set aside to do it, he has to make room in his schedule. “I can say, ‘I’d love to go to this meeting, but I can’t because I have to get that work done.’” You can’t have it all.

The work box has a hard stop each day at 6 p.m., when his family box begins. He’s strict about not letting last-minute deadlines or calls spill over into that box, where he spends time with his kids and his wife (to whom he is still happily married). And at 10 p.m., it’s time for bed. You might say it’s like clockwork.

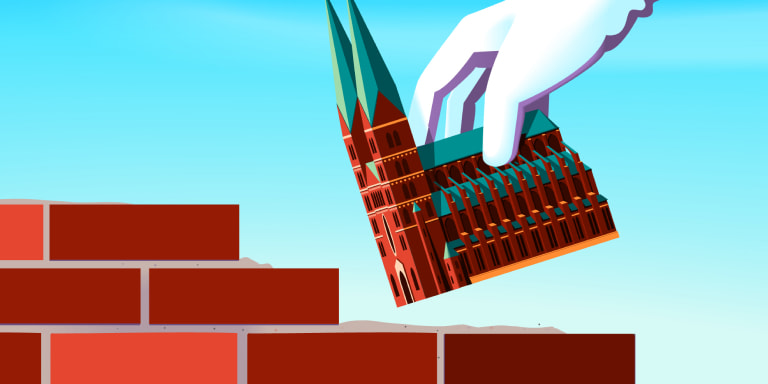

It takes resolution to create boxes and stick to them. Timeboxing requires having to say no often and holding firm under pressure. And of course, life can’t always fit into a box. There are moments when confining work to predetermined hours just isn’t possible, and for caretakers and others who have less predictable lives, this method may be more challenging. But using the principles of timeboxing, anyone can build walls around their schedule (even if those walls are necessarily adjustable). If your child goes to sleep at 8, schedule time with your partner for after their bedtime. If an elderly relative has physical therapy every Tuesday at 3, that can double as your Pilates box. The trick is to take control of what you can, when you can, rather than letting your responsibilities wash over you like a flooding river.

The trick is to take control of what you can, when you can, rather than letting your responsibilities wash over you like a flooding river.

This practice upholds the notion that you are in charge of your own happiness, that maintaining work-life balance, avoiding burnout, and finding the time to get all your work done is your job, not your company’s. Still, it’s essential for leaders to understand and accept that working people to the point of exhaustion rarely means they’ll do better work (and, in fact, often means they’ll be less productive ). Spataro says managers and executives should encourage employees to take ownership of their schedules and respect the boxes they erect. “You have to set the culture for that at the corporate level,” he says. “You have to have the senior-most leaders paint that picture and help people understand that, not only is this okay, this is what we want.” Satya Nadella has fostered that culture as CEO at Microsoft, telling his employees, like Spataro, that it’s okay to ignore an email over the weekend. “One of the things I’m at least getting better at,” Nadella says, “is being able to set that expectation.”

Ultimately, it’s about control, and being disciplined about the time you have to spend on what’s important to you. When you have only a 30-minute window to review a white paper and the rest of your time is accounted for, you’re less likely to get distracted by non-pertinent pings. If you have just an hour and a half set aside for dinner with an old friend from college, you can afford to silence Outlook and leave your phone in your pocket. After all, when the box ends, so does that time—so it’s up to you to make the most of it.

5 Ways to Start Timeboxing Right Now:

1. Accept that you can’t have it all.

We are all limited by time and space, and it’s impossible to do everything we want to. The sooner you accept that, the sooner you’ll be able to use the time you do have on what’s most important to you.

2. Pick 5.

Divide your life into three to five areas you want to spend your time on. They should be broad, such as family, community, health/wellbeing, and work. And don’t forget the foundation. “This all falls apart if you don’t get enough sleep,” Spataro says.

3. Make your schedule...

Write down how many minutes a week you are willing to give each area, then lay them out on a weekly schedule with as many precise start and stop times as you can. Some easy ones to start with: How much do you need to budget for sleep each night? How much time do you need to devote to work? Fill in the gaps with your other priorities.

4. ...and stick to it.

Boxes are enclosed for a reason. To make the most of timeboxing, be rigorous about staying within yours. It might not seem like a big deal to work 10 minutes past the end of your work box, but enforcing your constraints will crystallize the habit of making the most of the time you’ve allotted.

5. Know when to make exceptions.

Life happens, and it won’t always be possible to stick to an exact schedule. Maybe you’ve got an end-of-year presentation due to a client, and for the next three weeks you need to borrow time from the after-work hiking box to compensate. The key here is to consciously decide whether it’s worth it to make an exception, and to ensure that it’s a deviation, not the norm.